The single most valuable commodity in the business world is, and has always been, creativity. Especially in the arts. Because it is an inherent talent. Despite seminar-dispensed mental regimens intended “to encourage creative thinking,” true creativity cannot be taught by one person to another. It can only be trained, once found.

The single most valuable commodity in the business world is, and has always been, creativity. Especially in the arts. Because it is an inherent talent. Despite seminar-dispensed mental regimens intended “to encourage creative thinking,” true creativity cannot be taught by one person to another. It can only be trained, once found.

Modern businessmen understand that fact, though most refuse to admit it. Creativity— the spark that ignites all human innovation (translated in current business lingo as “outside the box thinking”)— is INVALUABLE in all fields of endeavor from simple arts and crafts up to deadly military operations. Creativity produces solutions. It invents new tools and processes to solve problems and achieve success.

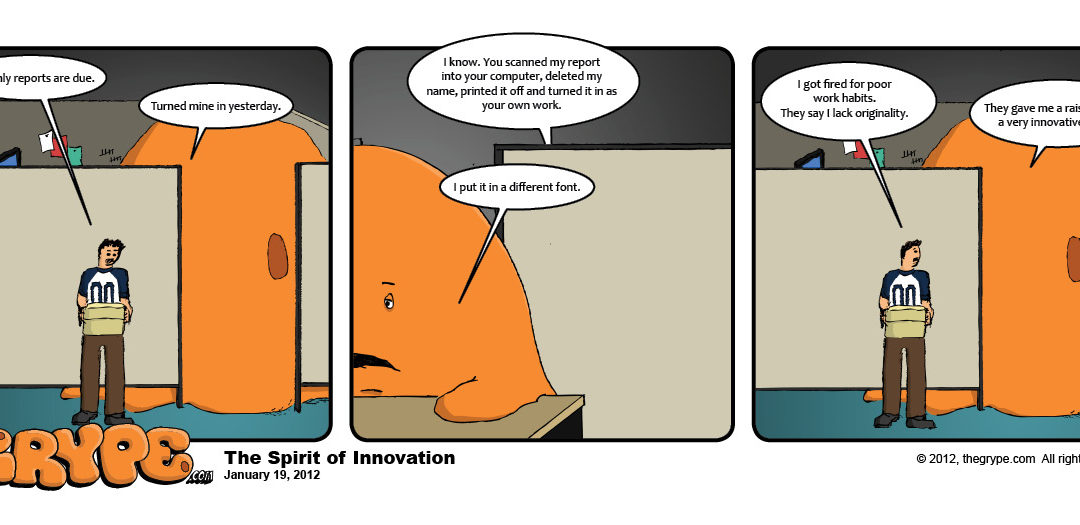

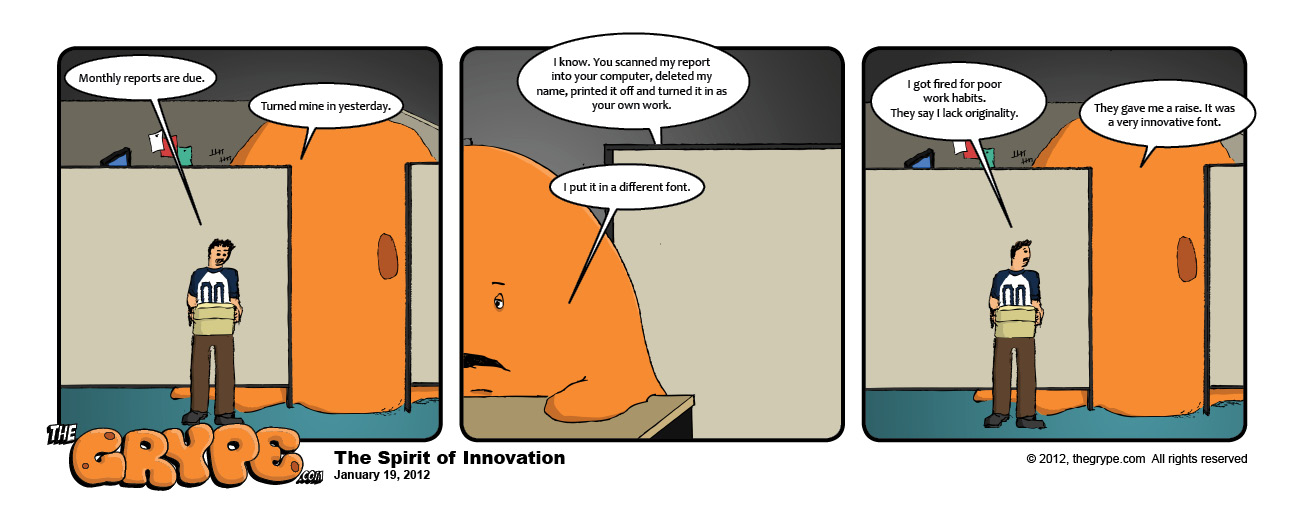

Those who possess it are both blessed and cursed in a business environment. Why? Because the manifestation of such creative ability is sometimes sporadic and intermittent, making it unreliable and essentially undetectable except when it situationally appears. That makes it a quality everyone wants to possess, but which is easily faked. Some who lack creativity will desperately disguise the fact by pirating the creative output of others, rebranding it as a product of their own invention; covertly picking the brains of truly creative people in their vicinity, they seek fresh raw material to mint into career-sustaining coinage. Such “creativity vampires” metaphorically attach themselves like lampreys to the best creators they know, parasitically leeching off the ideas of others (though this practice can backfire if the idea-thief fails to correctly understand the details of a purloined idea, ruining it through mistranslation).

Such thievery isn’t difficult. Creative people tend to take their own creativity for granted and essentially give it away, a trend which empowers an entire subclass of idea-thieves to exist, avariciously repackaging someone else’s concepts while basking in the reflected glow of the real innovator’s talent.

Since creativity is such an extremely valuable commodity, naturally corporate businesses seek to own and trade it for purposes of profit. But real creativity— ever elusive— cannot be elicited on demand. Ofttimes it requires a specific hospitable environment wherein it can flourish. Many corporate businessmen, if utterly lacking creativity themselves, don’t really understand what it is or where it comes from— only that it is an invaluable problem solver. They seek ways to quantify and measure it, to chart it and graph it and horde it for a rainy day. But that’s not how it works.

Unable, themselves, to successfully “create,” the suit-clad managerial corps of the business world occupy themselves trying to predict trends of innovation and identifying, appropriating, and merchandising fresh new ideas and concepts the moment they appear… often without the cooperation of the original creator.

The film, music, and publishing industries in particular are famous for over-inflating their corporate ranks with business-savvy but artistically talentless bean-counters, many of whom build whole careers around spearing someone else’s artistic work or creative concept then dragging it back to the communal corporate fire pit to render it down and drain every last drop of monetary value it possesses. Given an opportunity to support some creative NEW endeavor versus trying to recycle yesterday’s hackneyed concept and foisting it upon the market yet again… most of them will favor re-using something that worked in the past. Lacking the qualities of innovation and creativity themselves, they can’t tell if a new idea, concept, or artistic work is good or not. If they get suckered into wasting a zillion bucks supporting some supposedly-creative flop, or risk ham-handedly fouling an established well of creativity through mismanagement, expect their corporate star to plunge meteorically like a fin-less lawn dart (LTNS Michael Eisner, Pixar says “Hi”). Just remember— expecting an uncreative business executive to embrace innovation is like asking them to play a game of Russian Roulette with their career. Naturally, they’re frightened of what they don’t understand.

To the ranks of buttoned-down, pin-striped corporate memo-pushers it will always seem safer to crank out yet another awful franchise sequel than risk navigating the tempestuous waters of artistic creativity and innovation. Perhaps if real creativity was more common (and less lucrative), the corporate business world wouldn’t have such a love/hate relationship with it. Then maybe bad film remakes, endless regurgitated book series, and pathetic remixed cover songs wouldn’t plague us to the extent they do. And what a loss THAT would be.