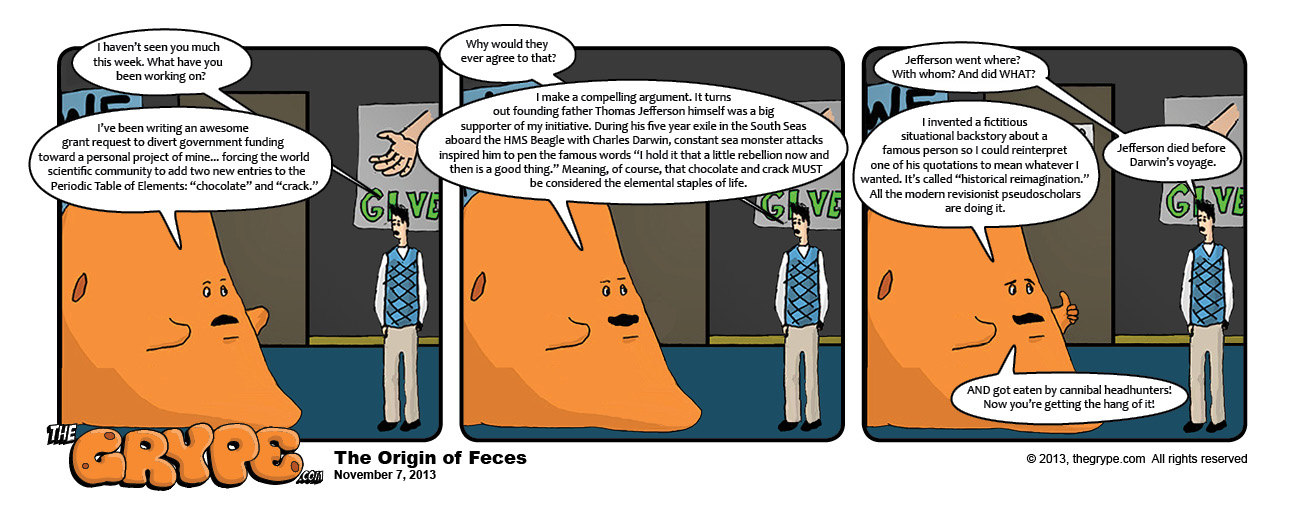

These days there seems to be lots of vitriol being slung around by various self-proclaimed geniuses and political pundits over the presumed opinions of America’s Founding Fathers— those “fathers” being the relatively small cadre of patriot leaders who formally broke ties with Great Britain and set our ancestors on the path to liberty. I find it interesting that the sacred memory of those great Americans is so-often invoked by corporate advertisers when pitching their wares and services— especially since most of the signers of the Declaration of Independence really didn’t have much good to say about corporations. Their direct experience was with British corporate monopolies such as the East India Company, whose strict regulation of such vital life-staples as tea was the inspiration for a pretty famous midnight protest event in Boston Harbor.

These days there seems to be lots of vitriol being slung around by various self-proclaimed geniuses and political pundits over the presumed opinions of America’s Founding Fathers— those “fathers” being the relatively small cadre of patriot leaders who formally broke ties with Great Britain and set our ancestors on the path to liberty. I find it interesting that the sacred memory of those great Americans is so-often invoked by corporate advertisers when pitching their wares and services— especially since most of the signers of the Declaration of Independence really didn’t have much good to say about corporations. Their direct experience was with British corporate monopolies such as the East India Company, whose strict regulation of such vital life-staples as tea was the inspiration for a pretty famous midnight protest event in Boston Harbor.

That’s why corporations were regulated so harshly by our nascent Federal government. One example: during the early years of our country, corporations were limited by law to an existence of only 20-30 years. Even within their limited lifespan, a particular corporation was allowed only to deal in one commodity; was not allowed to hold stock in other companies; and their total property holdings were strictly limited to what they needed to accomplish their business goals. Expansion and conglomeration were forbidden, as was diversifying corporate interests.

The most glaring difference between how our founding fathers treated corporations versus the inordinate sway modern corporations presently hold over public and private life in America is the simple fact that during the earliest days of our nation there were laws on the books that made any political contribution by corporations to any candidate for elected office, or any attempt to otherwise influence law-making, a criminal offense.

Originally the privilege of incorporation was granted specifically to support endeavors that directly benefited the public (like construction of roads or canals). By allowing shareholders to profit, incorporation encouraged the contribution of private capital toward such projects. But corporate charters could be revoked if laws were violated, and corporate owners and managers were responsible for criminal acts committed on the job. Citizen authority clauses limited capitalization, debts, land holdings, and ill-gotten gains: a company’s accounting books must be surrendered to a legislature upon request. Interlocking directorates were outlawed, and shareholders had the right to remove directors at will. In Europe, corporate charters had long protected directors and stockholders from liability for debts and harms caused by their corporations. But American legislators explicitly rejected this corporate shield.

In 1819 the U.S. Supreme Court tried to strip states of their chartering rights by overruling New Hampshire’s right to revoke a corporate charter; the bold attempt of the SCOTUS to subvert state corporate chartering laws inspired nineteen states to adopt new state constitutional amendments to circumvent the SCOTUS ruling. In 1855 the Supreme Court finally relented when in Dodge v. Woolsey it reaffirmed state’s powers over “artificial bodies.”

But corporations continued to fight against regulation intended to keep them honest, abusing their charters and becoming conglomerates and trusts to convert America’s resources into private fortunes, spawning factory systems and company towns. Political power and wealth was amassed by absentee owners, and community-rooted enterprises were pillaged and abandoned. Until at long last, in 2010, the SCOTUS ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 310 finally twisted the very Constitution itself into defending corporate interests by essentially declaring that corporations collectively held all the individual rights guaranteed to American citizens.

Nice going, SCOTUS! I’m sure you were well-compensated for your trouble. Our forefathers must be so proud.