Change that soap now. Mr Bloom’s hand unbuttoned his hip pocket swiftly and transferred the paperstuck soap to his inner handkerchief pocket. He stepped out of the carriage, replacing the newspaper his other hand still held.

Paltry funeral: coach and three carriages. It’s all the same. Pallbearers, gold reins, requiem mass, firing a volley. Pomp of death. Beyond the hind carriage a hawker stood by his barrow of cakes and fruit. Simnel cakes those are, stuck together: cakes for the dead. Dogbiscuits. Who ate them? Mourners coming out.

He followed his companions. Mr Kernan and Ned Lambert followed, Hynes walking after them. Corny Kelleher stood by the opened hearse and took out the two wreaths. He handed one to the boy.

Where is that child’s funeral disappeared to?

A team of horses passed from Finglas with toiling plodding tread, dragging through the funereal silence a creaking waggon on which lay a granite block. The waggoner marching at their head saluted.

Coffin now. Got here before us, dead as he is. Horse looking round at it with his plume skeowways. Dull eye: collar tight on his neck, pressing on a bloodvessel or something. Do they know what they cart out here every day? Must be twenty or thirty funerals every day. Then Mount Jerome for the protestants. Funerals all over the world everywhere every minute. Shovelling them under by the cartload doublequick. Thousands every hour. Too many in the world.

Mourners came out through the gates: woman and a girl. Leanjawed harpy, hard woman at a bargain, her bonnet awry. Girl’s face stained with dirt and tears, holding the woman’s arm, looking up at her for a sign to cry. Fish’s face, bloodless and livid.

The mutes shouldered the coffin and bore it in through the gates. So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of that bath. First the stiff: then the friends of the stiff. Corny Kelleher and the boy followed with their wreaths. Who is that beside them? Ah, the brother-in-law.

All walked after.

Martin Cunningham whispered:

—I was in mortal agony with you talking of suicide before Bloom.

—What? Mr Power whispered. How so?

—His father poisoned himself, Martin Cunningham whispered. Had the Queen’s hotel in Ennis. You heard him say he was going to Clare. Anniversary.

—O God! Mr Power whispered. First I heard of it. Poisoned himself?

He glanced behind him to where a face with dark thinking eyes followed towards the cardinal’s mausoleum. Speaking.

—Was he insured? Mr Bloom asked.

—I believe so, Mr Kernan answered. But the policy was heavily mortgaged. Martin is trying to get the youngster into Artane.

—How many children did he leave?

—Five. Ned Lambert says he’ll try to get one of the girls into Todd’s.

—A sad case, Mr Bloom said gently. Five young children.

—A great blow to the poor wife, Mr Kernan added.

—Indeed yes, Mr Bloom agreed.

Has the laugh at him now.

annotation:

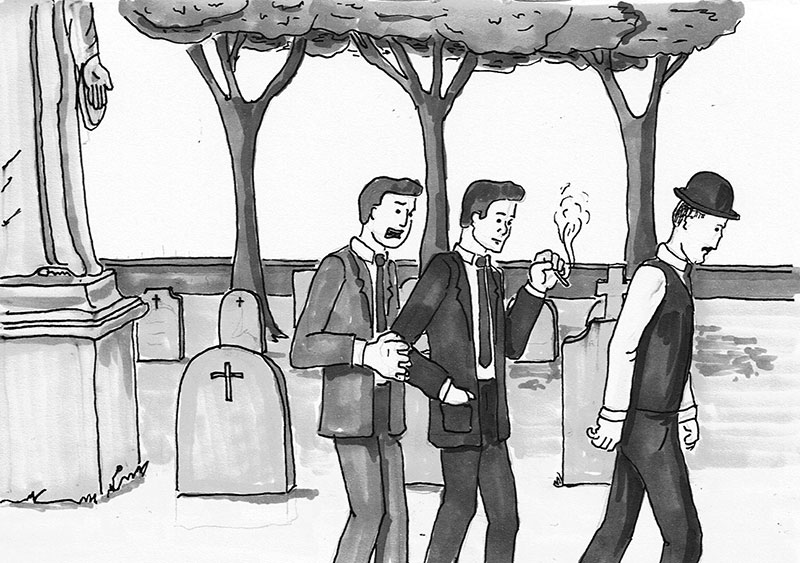

Again Bloom alludes to the previous less dour chapter, remarking on moving the soap from one pocket to the other. It’s almost as if Bloom is continually yearning to no longer be in his present position. Bloom’s thoughts seem to be constantly blurring the lines between the living people in the cemetery and the dead. at different points the living act like the dead, “The mutes shouldered the coffin and bore it in through the gates. So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of that bath. First the stiff: then the friends of the stiff.”, and sometimes the dead act like the living, “Coffin now. Got here before us, dead as he is.”. This device further establishes that Bloom is in the land of the dead, and the way his travel companions treat him as they talk about him behind his back makes clear his isolation. I thought I would further add to the feeling by putting a lit cigarette in Mr. Powers hands, adding a feeling of fire and brimstone. I also put a looming statue of Christ at the edge of the frame, an homage to the way Catholicism for better or worse frames Joyce’s life and writing.

Again Bloom alludes to the previous less dour chapter, remarking on moving the soap from one pocket to the other. It’s almost as if Bloom is continually yearning to no longer be in his present position. Bloom’s thoughts seem to be constantly blurring the lines between the living people in the cemetery and the dead. at different points the living act like the dead, “The mutes shouldered the coffin and bore it in through the gates. So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of that bath. First the stiff: then the friends of the stiff.”, and sometimes the dead act like the living, “Coffin now. Got here before us, dead as he is.”. This device further establishes that Bloom is in the land of the dead, and the way his travel companions treat him as they talk about him behind his back makes clear his isolation. I thought I would further add to the feeling by putting a lit cigarette in Mr. Powers hands, adding a feeling of fire and brimstone. I also put a looming statue of Christ at the edge of the frame, an homage to the way Catholicism for better or worse frames Joyce’s life and writing.