We’ve all heard the old saying “the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” Meaning that anyone confronted with a problem can reasonably expect to achieve a solution if they complain loudly enough (whereas those who silently suffer should expect no relief).

Letting out a squeak or two can definitely get you noticed, though in actual practice that’s not always the case. Sometimes being the loudest and most annoying member of a group is NOT the best thing to be. In a nest full of baby birds, chirping loudly might seem a good way to attract the attention of mama bird and thus be the first fed. But if the visitor currently looming over the nest turns out to be a hungry cat, then being noisiest is a good way to ensure that one is the first eaten. Don’t let anyone con you into buying that whole “if everyone gets it in the end, it doesn’t matter who goes first” line of nihilistic bullshit: when it comes to being eaten, LAST is always better. Just ask the Donner Party.

As children we were sometimes encouraged to voice our complaints (and tattle on our peers), but were paradoxically expected to shut up if our complaints became annoying or inconvenient to the authority figures in our vicinity. The squeaky wheel, it seems, does not always get the grease. On the contrary— sometimes the squeaky wheel gets spanked. It helps if one’s mode du complaint is less annoying than, say, the sound of fingernails on a blackboard. Or (ouch) tinfoil scraping across metal dental fillings. One must complain strategically, in a sympathetic manner, if one hopes to be heard. Anything else invites disdain, summary dismissal, and the possibility of perfectly good playtime wasted while sitting with one’s nose in the corner.

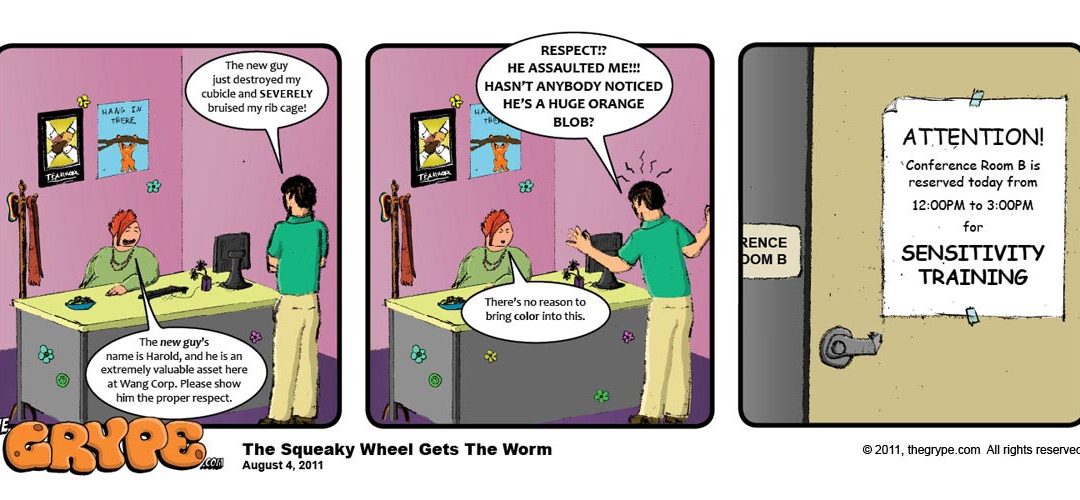

As adults in the workplace, little has changed with the above scenario. One must be cautious when voicing one’s disapproval of workplace conditions or fellow employees, lest one invoke the ire of the great managerial powers-on-high. Delicacy is advised. Loud and incessant complaints don’t usually ingratiate the complainer with upper management, and if repeated often and loudly enough such actions risk calling down the wrath of upper management— perhaps in the form of a career-skewering annotation to your employee file that reads: “NOT A TEAM PLAYER.” It may not sound too threatening, but (as any HR professional will tell you) earning that particular notation is similar to committing vocational suicide, but slower and messier.

A tip: when managers tell you to put your complaints in writing, that’s not always what they really want. Because if you actually put your complaints in writing, it means that 1) there is now permanent evidence on file that a complaint has been formally registered and 2) now someone is actually going to have to do something about it.

The difference between a casual request and a FORMAL COMPLAINT™ is that a casual request enlists the concerned aid of the requestee in a friendly supervisory role… yet by keeping the context of the complaint informal, it allows some creative flexibility in alleviating the problem. Whereas a FORMAL COMPLAINT™ is made “for the record” and as such it demands action, compelling the supervisor to respond along strict policy lines and forcing his hand. Action must follow… but that’s not always entirely beneficial for the complainant, should the resulting action turn out to be a giant pain-in-the-ass for all concerned.

In the new politically-correct (read: Liticaphobic, i.e: “afflicted with a fear of litigation”) workplace, things have changed. People have become hyper-litiginous; practically any annoyance or instance of rude behavior can be construed as provocation for an indignant phone call to some ambulance-chaser. An ever-expanding fraternity of ambitious lawyers continue to fund their lifestyles by milking the fall-out from some ridiculous bit of employee misbehavior that wouldn’t earn an errant toddler more than a short time-out in any well-run suburban kindergarden.

In a perfect corporate world, would every employee be content, happy and well-adjusted? Probably not; there are some personalities who cannot manage any of those things, even under the best conditions: winnowing jerks who constantly harangue restaurant managers for free food if the service is less than perfect (or even if it is), or demand free hotel rooms even though the screwed-up reservations may have been their own fault. Such opportunists aren’t the selfless advocates of public outrage they imagine themselves to be; the worst examples of such connivance can be pretty pathetic.

Sometimes an earnest whistleblower CAN make a difference, the forces of truth and altruism triumphing over the slack-jawed vapidity of corporate indifference. But be warned: when traversing the minefield of any corporate complaint department, be prepared for the possibility that the consequences might not be precisely what you wanted: instead of a freshly-greased axle, sometimes there isn’t any grease at all. Or the best you might achieve is a perfunctory mouthful of worm.

It can be a zero-sum game. And if taken too far, what the squeaky wheel usually gets is “the sack.”