So, in the aftermath of the recent tragic church shooting in South Carolina, the controversy over the continued presence of the Confederate battle flag on state property has again arisen.

So, in the aftermath of the recent tragic church shooting in South Carolina, the controversy over the continued presence of the Confederate battle flag on state property has again arisen.

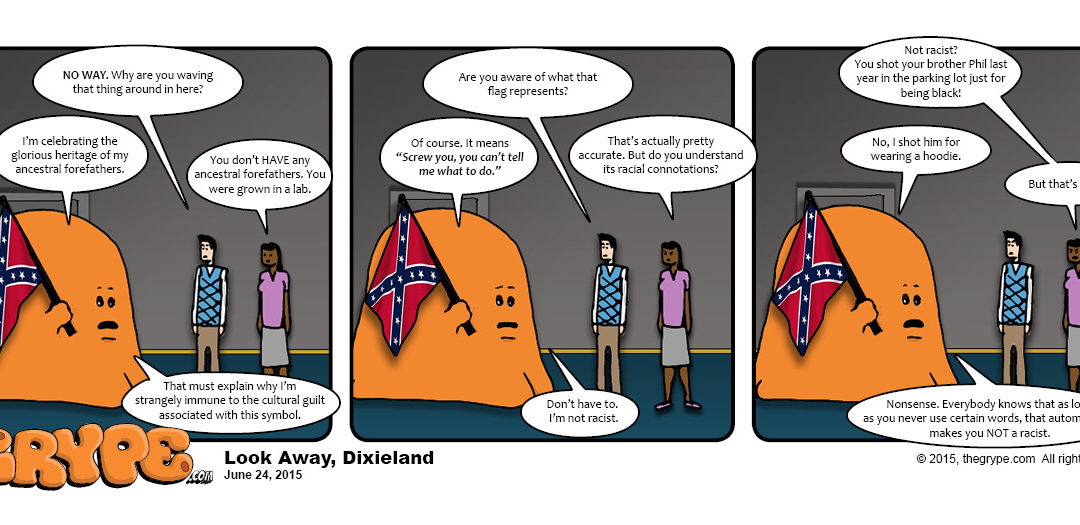

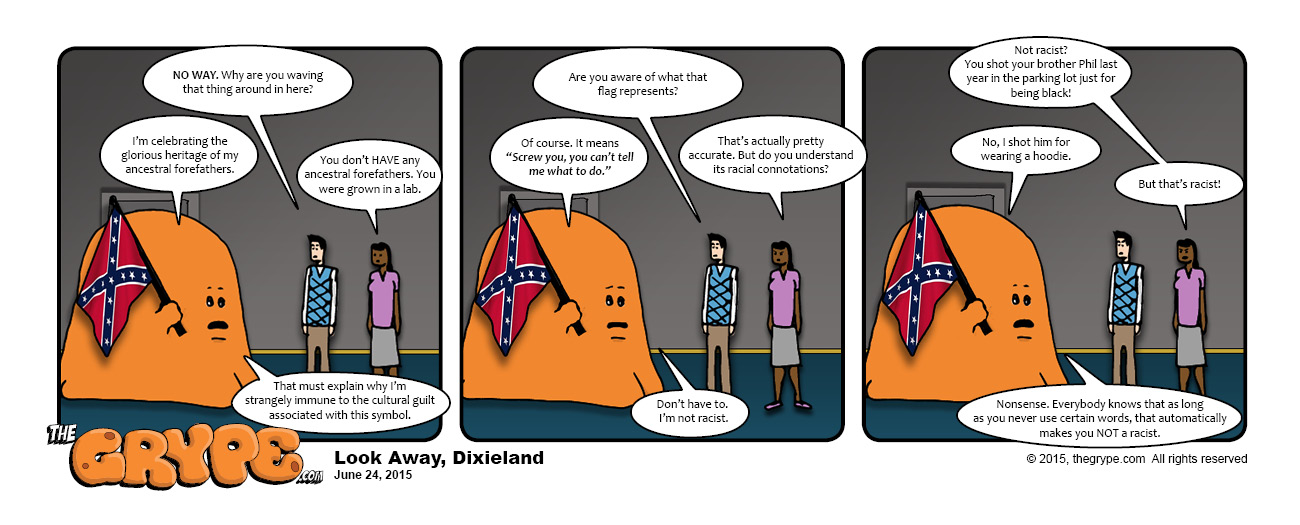

I don’t understand why it’s suddenly become such a flashpoint for such vicious opinions. I just consider it a cultural mile marker for our changing society. When enough people decide it needs to come down, I presume it will. The trouble with that flag is that it obviously symbolizes different things to different people. Worse yet, that PARTICULAR flag has ALWAYS—in every incarnation—represented the same sentiment:

“Screw you, you can’t tell me what to do.”

Those who adopt it as a personal totem— be it for historical, cultural, ideological or purely racist reasons— do so for that exact reason. Those aren’t exactly the kind of people who are going to cave in to cultural pressures to give up that symbol (and its unspoken mantra) swiftly or easily.

My First Amendment sensitivities balk whenever someone demands that another must shut up or otherwise be censored for being offensive. But I also understand why it’s illegal to shout “fire!” in a crowded theater, too. To incite, to trigger, to insult, to demean… these aren’t the noblest reasons to express one’s freedom of speech. The culture will decide, though.

Even the historical symbolism of that flag is open to interpretation. One man’s “treason” is another man’s “resistance to tyranny.” That’s nothing new. I know the history behind it; much depends on if one focuses on the specific reasons why the Confederacy split, vs. whether or not they had the legitimate right to split from the Union in the first place, and if that right was revoked lawfully or not.

Again: perspective.

But… If a symbol reaches the point where it offends a large enough portion of the population, one can reasonably expect that symbol to lose its license as a public brand.

That particular flag has been around for 153 years. Naturally, over such a long period, it has become subject to many historical and symbolic meanings. It still is, today. Some people see it as a symbol of the south’s fight to preserve slavery, and, by extension, of slavery itself. Others see it as a symbol of the south’s fight against dastardly Yankee oppression (a popular one, that). Some see it as the symbol of a revived south that survived Reconstruction, made it through Radical Reconstruction and endured the much-hated Redemption eras that followed the Civil War. Some see it as a symbol of a rebellious spirit, or refusal to submit to unjust persecution by one’s enemies. Some see it as a symbol of the collective southern spirit or culture.

It’s meant a lot of things over the century-and-a-half that it has existed as a symbol. Unfortunately, part of its history is that it was unofficially adopted as a symbolic flag to represent the second, post-Reconstruction re-formation of the KKK in 1916. That pretty much sealed its fate as being directly attached to bigotry and racial (and religious) intolerance in the 20th century, a connotation that it has continued to carry and probably will never shed. Racists and radical extremists of various types have historically rallied around it in the post-Civil War era. That continues, and has probably ensured that it can never be redeemed from the stain of racial violence in popular culture.

I suppose my personal position on the current controversy is this:

I think we must always be cautious about selecting what evidence of what parts of our history we choose to hide or deny because they make us feel uncomfortable. Lest we sanitize our past so completely that we forget where we come from. The only profitable way for a society to deal with its history is to study it, understand it, and try to fully comprehend its meaning and learn everything from it that CAN be learned.

We are not all heroes, nor are we all monsters. Good people can do brave things fighting for bad causes, just as bad people can do awful things fighting for good causes, and vice versa in infinite combinations. The measure of good and bad will shift through the years, until it becomes far easier to simply render hopelessly modern moral judgments— be they unduly complimentary or unfairly insulting— atop people whose era simply did not avail them the same moral certitude that some would now dare claim, after a fast scan of a Wikipedia article or opinionated website.

Let us beware trying to hide the truth about the past, unpleasant or unpopular though it may be. Lest someday, new oppressors should build on that precedent to deny that the unpleasantries of the past ever existed in the first place, as an excuse to revive them for an unsuspecting modern audience.

C’est la histoire. Tels sont les faits concrets.