A thin gray morning dawns across the mighty metropolis, and I rise to face the day within the confines of my little cube.

It’s a space on the second floor of what was once a deli in Midtown near the Roosevelt Hotel. A lot of office space on the upper floors of commercial buildings got converted to extra living spaces in the initial influx immediately following annexation. For decades before the split happened, venture capitalists and forward-thinking types had been speculating how perfect the world could be if only they were allowed to invent a brand-new-society from scratch. That theory surmised that if you just let the genius CEOs of some big tech company set the whole thing up, it would flourish the same way as Silicon Valley. There was a lot of wild speculation in those days about a barge Google had launched in the San Francisco Bay— people believed it might be the early stages of a floating city, a new style of ocean-borne “aqua-state,” intended to function beyond the reach of government oversight and out-of-control taxation.

In the end, it just turned out to be yet more data storage… but it planted the idea of a capitalist meritocracy utopia in the minds of a lot of people. I remember watching a documentary about it: the new wave of would-be social engineers posited that most of society’s ills were endemic and too deeply entrenched to repair, but if given a clean-enough slate the smartest people would be able to devise a new system where all individuals would invariably rise according to nothing other than their own merit. To truly understand the sentiment, though, you need to know what people were like, right before annexation: postmodernism had introduced and ultimately popularized the idea that everyone could have their own “individual” truth. That idea was originally supposed to bring about an age of heightened understanding and acceptance… except we-the-people hadn’t exactly gotten over our modernistic predisposition for believing we were already right about everything, and the internet— particularly the social aspect of it— allowed people to discover and ally with others who felt exactly the same way as they did about any given topic. We grew very good at the “distillation of cohesive ideas” part of postmodernism, except we glossed over the whole “entertain the validity of other people’s ideas” part of it. We’d actually gone the other way. Postmodernism (or at least the bastardized version of it we’d all come to practice) had fragmented us even further. All arguments were no longer about analyzing and measuring facts, they were about the sanctity of people’s subjective interpretation of the facts, and the media wasn’t helping. They were profiting from it.

Eventually a conciliatory centrist view of communication and compromise gained some popularity, but not before any such “middle-of-the-road” thinking had formally been labeled cowardly and even radical by the Balkinized extremists. Political candidates who dared mention compromise or were willing to consider an alternate perspective were dismissed as insane. The gaps between popular perspectives continued to grow ever wider, but amidst the increasing polarization there arose a tiny culture of defiant centrists. “Annexation” was the perfect rallying cry for people like that. People like me, honestly. I lived in the city before it fractured from the mainland, but when it happened, I welcomed it.

This morning though, in my white polycarbonate-walled 10′ x 10′ living space, I’m not so much in love with the whole idea anymore. I suppose I shouldn’t say 10′ x 10′ since we all finally went metric (because that system is supposedly so much easier to use), but I just can’t get accustomed to it. Honestly— it’s not fair to call the walls “white” either. They are the dingy yellow-white that plastic takes on when left unpainted and exposed to sunlight for a few years. The color of computer cases from the early 1990’s. That’s something you learn as you get older: the sun wears everything out. I concede that its probably less than fair to complain about my space. 10′ x 10′ is the standard size living space in the wasteland, but at least mine faces the window to the street. It was the luck of the draw. There are 16 other habitats on my floor, none of which have a window. I wonder if their plastic is the same yellowish shade as mine? At 6 feet tall, I find the space confining, though I’ve heard they’re reconfiguring some downtown habitats to be 9′ x 9′ (or 2.74 meters, rather).

That’s the problem with this place, though: everyone is still stuck in the old-world-mindset while pretending to possess all these shiny-new-world ideals. If we were REALLY going to switch to metric, why not just make it an even 3 meters? Nope. We’ll devise the idea in feet, and then expend additional effort to convert it over to meters after the fact, all to conserve effort because metric is somehow easier. Wasteland logic. What’s even scarier to me is that people are still moving here. They need MORE housing here. I wish I could pretend I didn’t know who the new arrivals were, but I know exactly. It’s the exact same type of people who have been moving here since the very beginning. Because if you can sell someone an ideology or the idea of a lifestyle, it doesn’t matter what the actual particulars of your product happen to be. All you need do is convince people that they want to be the type of person that buys what you’re selling. Apple did it brilliantly, famously creating the most effective model for such targeted social group marketing ever devised, so almost immediately after the annexation BHN reached out to Silicon Valley for help marketing NYC as a product.

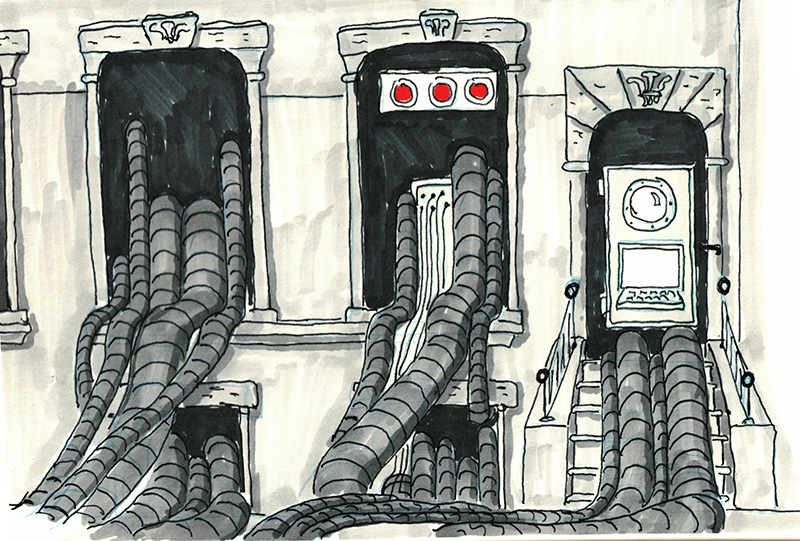

First they had to offer relocation money and a way out of NYC for all who wanted to remain citizens of the territorial United States… that exodus freed up a lot of city real estate. The largest tech companies bought out most of the less-desirable parts of Brooklyn and Queens. These days, all but a few of the old neighborhoods there are ghost towns, their houses converted to data-storage-centers or render farms full of humming server racks, empty streets lined with gutted brownstones, cables running in and out of every opening. The buildings look like they’re on life support, although in truth they’re probably better-maintained than they were when there were people living in them.

The last of the old homestead rent controls were abolished, so it wasn’t hard to get people to abandon their shabby apartments across the bridges. BHN was offering newly-refurbished 10′ x 10’s in Manhattan for much less than the old dumps people were living in, with the option of expanding into additional 10′ x 10’s per family member, up to a maximum of 40′ x 40′. That may not seem like a lot, but many of the lower-income families were already living in less space than that, if you factor the personal space ratio according to the number of people with whom they shared a dwelling. That was another stroke of genius: automatic citizenship for anyone who could prove they had permanent residence in one of the boroughs and was willing to take a government job. That was one-half of the strategy— it created a public works employee-network of fiercely loyal workers. Wasteland was a haven, a way for them to stop living in constant fear. The other half of the strategy was to reach out to the disenfranchised young self-starter subculture. It was a clarion call to everyone who felt oppressed by a system that seemed not to care about them anyway: “Come to New York, no one here will stand in your way!” Wannabe tech geniuses, impatient entrepreneurs, and libertarians flooded the bridges and tunnels to embrace citizenship in a brave new country, one that claimed to care little about such impediments as regulations or tax money.

Of course, we soon learned our new country cared even less about our roads, sanitation, and housing maintenance.