For some reason there has always been a weird disconnect between comic book superheroes and film media. Which makes little sense, since heroic literary characters of the same archetype (Zorro, Tarzan, The Scarlet Pimpernel, etc.) have done pretty well in various film incarnations, despite their outlandish similarity to comic book heroes of the same vein. By “done pretty well” I refer to the faithfulness of their film incarnations to the original source material. Meanwhile, comic book superheroes rarely make it to the live screen without being horribly (and, usually, inappropriately) revamped and retooled into completely different creations. Creations that usually fail to satisfy.

For some reason there has always been a weird disconnect between comic book superheroes and film media. Which makes little sense, since heroic literary characters of the same archetype (Zorro, Tarzan, The Scarlet Pimpernel, etc.) have done pretty well in various film incarnations, despite their outlandish similarity to comic book heroes of the same vein. By “done pretty well” I refer to the faithfulness of their film incarnations to the original source material. Meanwhile, comic book superheroes rarely make it to the live screen without being horribly (and, usually, inappropriately) revamped and retooled into completely different creations. Creations that usually fail to satisfy.

I suspect the problem lies in the categorization of the source material itself. Books are books, and their contents, literature; whereas comic books originated as an inexpensive entertainment mostly intended for kids, printed on rough pulp stock garishly depicted in the cheapest four-color process of the day. Comics were meant to be read and thrown away (which is why mint condition comics from the 1930’s and 1940’s are prized by collectors today). Their covers trumpeted words like “Fun” and “Amazing” and “Action” in huge splashy fonts across the title banner. Superheroes were the biggest, brightest, flashiest characters of all, always larger than life… but infused with a raw childish glee. Simple plots, minimal dialogue, and fast action: that was the winning formula of the golden and silver ages of comic publishing.

It’s long been believed in the hallowed halls of film and broadcasting that comic books are strictly kid’s stuff. So when adapting comic book superheroes into film media, that is the approach too often taken by those involved– always to the detriment (and failure) of the adaptation.

But superhero comics— even the silliest and most immature of the lot— have always been taken seriously, if by no one else than by their faithful readers. Each fictional superheroic milieu exists as its own domain, bound by its unique inherent logic. If those who adapt that material take the time to understand— and remain true to— that logic, the end result will satisfy and embody the essence of that superhero experience.

But if not— then woe to any who dare adapt a superhero comic by trying to “elevate it” above the inherent rules and requirements of its source. You cannot do a superhero adaptation justice by steeping it in irony, while laughing at it behind your hand– especially if you don’t really understand why the source material is anything other than a big dumb joke intended for children. You might successfully parody it or devolve it to satire, and such a mockery might even be popular for a year or so until the laughter wears thin. But those laughing won’t be real fans; they’ll be those who mock the costumed superhero genre because they find it inherently laughable. They can’t appreciate the childish wonder and simplicity that were the roots the genre, nor can they accept the depth and complexity that has since infused superhero comics, evolving them into an art form that can readily compete with the most powerful examples of traditional literature; one full of the same philosophical resonance and inspiring characterization found in the most relevant of modern novels today.

Over the past 85 years of film and television, the only decent superhero adaptations were those which approached the subject matter with the utmost seriousness and took earnest care to preserve the unique elements that encapsulate the look, the spirit, and the underlying (albeit completely unreal) superhero logic that breathes urgency, relevance, truth— and ultimately, LIFE— into a fictional world that allows for the existence of such strange and wonderful anomalies as masked, costumed, super-powered crime fighters.

Studio executives and artists who can neither grasp nor accept the necessary unreality of such an adaptation will always strive to re-tool the comic book superhero into something more “realistic” and “less outlandish,” in the mistaken assumption that to attract and satisfy a “normal” audience, some supposedly-irrational elements common to superhero comics must be eliminated and the entire premise brought closer to real-world interaction. Costumes will be subdued or minimized; masks will be eliminated or taken off; larger-than-life set pieces will be re-imagined into something more mundane and realistically commonplace.

That is almost always a mistake; if such elements are changed, they must be replaced with satisfactory variants. You cannot take away the mask, or the cape, or the secret headquarters, without losing part of what makes the superhero unique and defines his character.

Nor should the adaptation completely abandon the realm of belief by pushing the superhero into an impossible world of bizarre impressionist scenery and ridiculous colors intended to suggest those found in four-color comic print. That’s a cheat; it completely gives up on the adaptation by resorting to artifice, slick trickery intended to excuse the unreality of the material by blaming its original format. A skilled director might successfully copy the style of an original comic by translating it into the “hyper-real”— but he shouldn’t surrender and diminish the entire exercise by just flattening it out and emulating a comic palette. That cheapens it without doing the original material justice.

Nor must everything therein be grim and humorless; but the humor that emerges within that world must be a part of that world; it cannot be laughter from outside, at that world’s expense.

Above all, every element of the superhero character and the world in which he dwells must be taken seriously, by all involved, or the entire project will ultimately ring false. Certain film and television directors have lately been able to succeed in this area, some more so than others. But to do so, those who would attempt such an adaptation must be fearlessly devoted to the original comic of origin.

Fearless. Which brings me to my review of the new NetFlix series, Daredevil.

Unlike a few recent television superhero adaptations which seem desperate to change the interactive dynamic of the comic books upon which they are based by unnecessarily altering seminal traits of the superheroes involved, and surrounding them with gobs of extra characters to shamelessly transform the adaptations into ensemble pieces of soap opera complexity (a hold over from the “focus more on the day-to-day life and relationships of the heroes than on the super stuff” trend of recent adaptations), Daredevil gets it mostly right.

It remains surprisingly true to the original comic book series. The main characters are recognizable, the action is believable (but still heightened enough to qualify as “super”), the fight scenes are amazingly well-crafted, and the plotting, though sluggish (even glacial) at times, eventually gets there. This first series functions as a 13-hour-long extended origin tale, and really takes its time getting to the last shot of the series— the big pay off costume pose. It’s a slow burn, but well worth it.

Charlie Cox is a solid choice to play Matt Murdock / Daredevil, a blind-but-superpowered lawyer who fights crime on the side. The series chronicles the character’s origin, juxtaposed with the rise of crime lord Wilson Fisk (whom comic fans know as The Kingpin), convincingly played by Vincent D’Onofrio. Deborah Ann Woll is believable as Karen Page and Elden Henson is adequate (admittedly with a few good moments) as Foggy Nelson.

The series creator is Drew Goddard, and the showrunner is Stephen DeKnight— both BtVS alumni during Joss Whedon’s WB/UPN tenure— which explains a lot. The same intricate plotting punctuated by sudden turnarounds and dramatic plot twistiness, long familiar to Buffy and Angel fans, abounds.

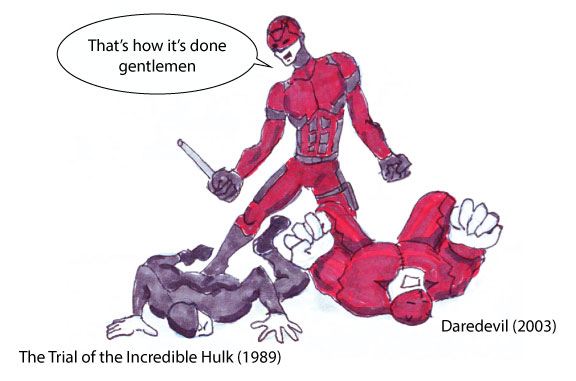

It’s a quiet adaptation, and one that definitely needs a second season to really get its feet under itself (another signature quality of the Whedon television ouvre). But it’s a highly successful relaunch of a superhero whose video legacy was almost ruined by a few half-assed appearances in desperate 1980’s Hulk TV movies and Ben Afflecks’ self-indulgent scenery-chewing film version. Let us never speak of those adaptations ever again.

I would have liked to see Matt Murdock’s trademark red hair on the character. But for some reason, nowadays all male TV superheroes are brunette with beard stubble. Even the blond and ginger ones. Nonetheless, I’ve been reading Daredevil comics since the mid-1970’s, and this is him. The Man Without Fear.

I’m hooked.