It’s long been a traditional introductory rite for college students to serve internships at prestigious firms to gain invaluable real-life experience, potentially leading to future employment. Such internships— paid and unpaid— are a well-established part of the post-graduate transition process between collegiate life and the private sector.

It’s long been a traditional introductory rite for college students to serve internships at prestigious firms to gain invaluable real-life experience, potentially leading to future employment. Such internships— paid and unpaid— are a well-established part of the post-graduate transition process between collegiate life and the private sector.

According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, 63 percent of the class of 2013 did an internship during college, almost half of which were unpaid. Okay, so being an intern is a good way to earn college credit while wetting your feet at a company in your chosen field. No one disputes the value of on-the-job experience, even working for a company that might not hire you.

But when the intern system keeps hopeful grads perpetually on the hook— working for free for an inordinate amount of time, even after graduation— the waters get murkier. There seem to be lots of unscrupulous companies eager to pad their labor force by getting clueless kids to work for free as unpaid slave labor.

One sector where this practice rears its ugly head is entertainment media. A growing number of regional theaters, television production companies and film studios regularly supplement their employee pool with fresh-faced recent grads eager to get their foot in the door in the competitive entertainment industry.

Lots of these interns wind up doing endless grunt work for little educational benefit and zero pay as part of a cyclical labor mill of unpaid interns doing work formerly done by paid staff — a serious violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act. This modern take on the indentured servitude model lures interns by promising a supposedly “unique learning environment” and the chance to experience the daily challenges associated with their field while making “important future industry contacts.” In exchange they carry the same workload as well-compensated production professionals. The fashion industry is another offender— a New York federal judge recently approved a $450,000 settlement between Elite Model Management and former interns who were allegedly made to do the work of employees for no pay in the largest settlement of an intern class action, ever.

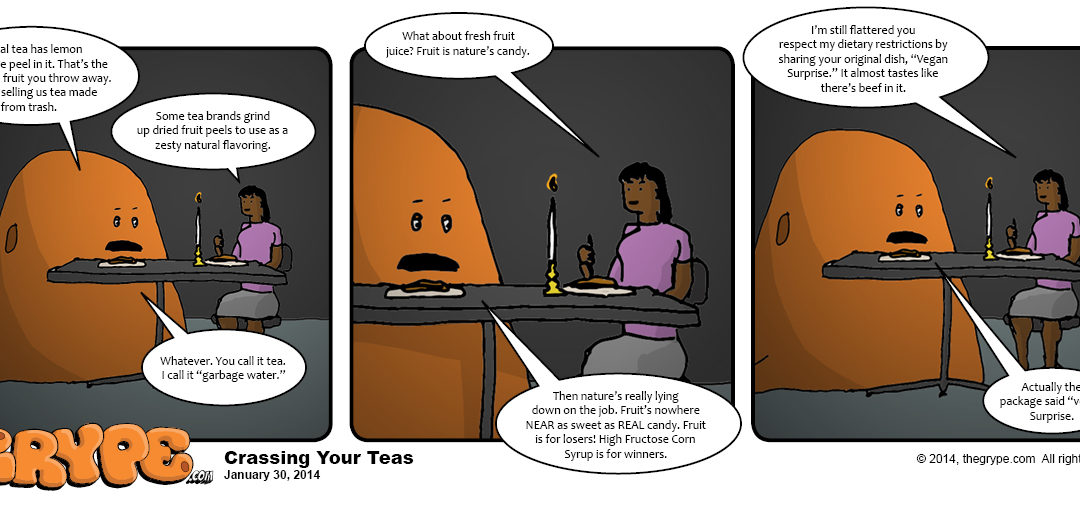

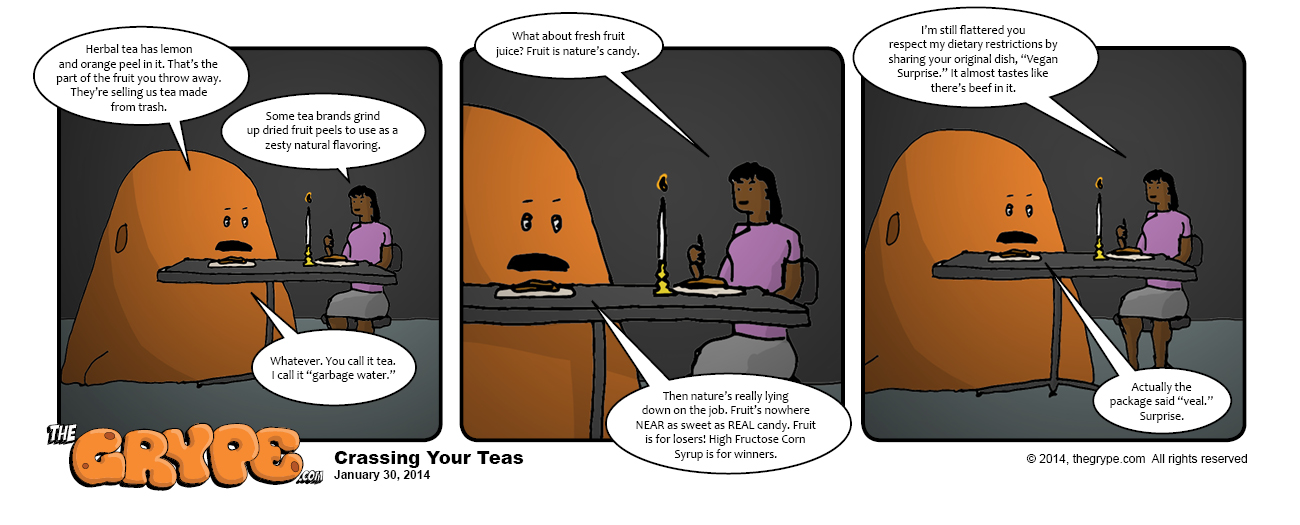

Another nasty flavor of the “free labor” racket is work that is done “on spec.”

“Spec” is slang for “work done on a speculative basis.” That’s when a customer or client asks for work to be done, even though no fee has been contracted or agreed upon. Spec work requires the worker to invest time, talent, and resources doing a project with no guarantee of payment. This brand of “I expect a free taste before I’ll commit to taking a bite” can turn ugly fast, leaving the worker empty-handed even though the client makes full use of the fruits of that worker’s labor—essentially stealing someone else’s work in exchange for nothing.

There’s been a serious ruckus lately in the film industry over the sad treatment of digital FX companies, and some are now being forced to work on spec (or for a theoretical share of film profits) just to land contracts and stay in business. After near-bankruptcy forced the closing of its Florida facility, Digital Domain traded 10 million dollars in free FX work (at cost) as part of a deal that made them co-producers of Ender’s Game. Lionsgate— the studio that actually produced the film— only paid for 20% of its cost. But when that film bombed, Digital Domain wound up 5 million dollars in the red, crushing the company at essentially the same moment it earned an Oscar nomination for Iron Man 3.

Awards don’t pay to keep the lights on, and working for nothing seldom pays off in the long run.