Episode 6 - Hades

—Come on, Simon.

—After you, Mr Bloom said.

Mr Dedalus covered himself quickly and got in, saying:

–Yes, yes.

—Are we all here now? Martin Cunningham asked. Come along, Bloom.

Mr Bloom entered and sat in the vacant place. He pulled the door to after him and slammed it twice till it shut tight. He passed an arm through the armstrap and looked seriously from the open carriagewindow at the lowered blinds of the avenue. One dragged aside: an old woman peeping. Nose whiteflattened against the pane. Thanking her stars she was passed over. Extraordinary the interest they take in a corpse. Glad to see us go we give them such trouble coming. Job seems to suit them. Huggermugger in corners. Slop about in slipperslappers for fear he’d wake. Then getting it ready. Laying it out. Molly and Mrs Fleming making the bed. Pull it more to your side. Our windingsheet. Never know who will touch you dead. Wash and shampoo. I believe they clip the nails and the hair. Keep a bit in an envelope. Grows all the same after. Unclean job.

All waited. Nothing was said. Stowing in the wreaths probably. I am sitting on something hard. Ah, that soap: in my hip pocket. Better shift it out of that. Wait for an opportunity.

All waited. Then wheels were heard from in front, turning: then nearer: then horses’ hoofs. A jolt. Their carriage began to move, creaking and swaying. Other hoofs and creaking wheels started behind. The blinds of the avenue passed and number nine with its craped knocker, door ajar. At walking pace.

They waited still, their knees jogging, till they had turned and were passing along the tramtracks. Tritonville road. Quicker. The wheels rattled rolling over the cobbled causeway and the crazy glasses shook rattling in the doorframes.

—What way is he taking us? Mr Power asked through both windows.

—Irishtown, Martin Cunningham said. Ringsend. Brunswick street.

Mr Dedalus nodded, looking out.

—That’s a fine old custom, he said. I am glad to see it has not died out.

All watched awhile through their windows caps and hats lifted by passers. Respect. The carriage swerved from the tramtrack to the smoother road past Watery lane. Mr Bloom at gaze saw a lithe young man, clad in mourning, a wide hat.

—There’s a friend of yours gone by, Dedalus, he said.

—Who is that?

—Your son and heir.

—Where is he? Mr Dedalus said, stretching over across.

The carriage, passing the open drains and mounds of rippedup roadway before the tenement houses, lurched round the corner and, swerving back to the tramtrack, rolled on noisily with chattering wheels. Mr Dedalus fell back, saying:

—Was that Mulligan cad with him? His fidus Achates!

—No, Mr Bloom said. He was alone.

—Down with his aunt Sally, I suppose, Mr Dedalus said, the Goulding faction, the drunken little costdrawer and Crissie, papa’s little lump of dung, the wise child that knows her own father.

Mr Bloom smiled joylessly on Ringsend road. Wallace Bros: the bottleworks: Dodder bridge.

Richie Goulding and the legal bag. Goulding, Collis and Ward he calls the firm. His jokes are getting a bit damp. Great card he was. Waltzing in Stamer street with Ignatius Gallaher on a Sunday morning, the landlady’s two hats pinned on his head. Out on the rampage all night. Beginning to tell on him now: that backache of his, I fear. Wife ironing his back. Thinks he’ll cure it with pills. All breadcrumbs they are. About six hundred per cent profit.

—He’s in with a lowdown crowd, Mr Dedalus snarled. That Mulligan is a contaminated bloody doubledyed ruffian by all accounts. His name stinks all over Dublin. But with the help of God and His blessed mother I’ll make it my business to write a letter one of those days to his mother or his aunt or whatever she is that will open her eye as wide as a gate. I’ll tickle his catastrophe, believe you me.

He cried above the clatter of the wheels:

—I won’t have her bastard of a nephew ruin my son. A counterjumper’s son. Selling tapes in my cousin, Peter Paul M’Swiney’s. Not likely.

He ceased. Mr Bloom glanced from his angry moustache to Mr Power’s mild face and Martin Cunningham’s eyes and beard, gravely shaking. Noisy selfwilled man. Full of his son. He is right. Something to hand on. If little Rudy had lived. See him grow up. Hear his voice in the house. Walking beside Molly in an Eton suit. My son. Me in his eyes. Strange feeling it would be. From me. Just a chance. Must have been that morning in Raymond terrace she was at the window watching the two dogs at it by the wall of the cease to do evil. And the sergeant grinning up. She had that cream gown on with the rip she never stitched. Give us a touch, Poldy. God, I’m dying for it. How life begins.

Got big then. Had to refuse the Greystones concert. My son inside her. I could have helped him on in life. I could. Make him independent. Learn German too.

—Are we late? Mr Power asked.

—Ten minutes, Martin Cunningham said, looking at his watch.

Molly. Milly. Same thing watered down. Her tomboy oaths. O jumping Jupiter! Ye gods and little fishes! Still, she’s a dear girl. Soon be a woman. Mullingar. Dearest Papli. Young student. Yes, yes: a woman too. Life, life.

The carriage heeled over and back, their four trunks swaying.

—Corny might have given us a more commodious yoke, Mr Power said.

—He might, Mr Dedalus said, if he hadn’t that squint troubling him. Do you follow me?

He closed his left eye. Martin Cunningham began to brush away crustcrumbs from under his thighs.

—What is this, he said, in the name of God? Crumbs?

—Someone seems to have been making a picnic party here lately, Mr Power said.

All raised their thighs and eyed with disfavour the mildewed buttonless leather of the seats. Mr Dedalus, twisting his nose, frowned downward and said:

—Unless I’m greatly mistaken. What do you think, Martin?

—It struck me too, Martin Cunningham said.

Mr Bloom set his thigh down. Glad I took that bath. Feel my feet quite clean. But I wish Mrs Fleming had darned these socks better.

Mr Dedalus sighed resignedly.

—After all, he said, it’s the most natural thing in the world.

—Did Tom Kernan turn up? Martin Cunningham asked, twirling the peak of his beard gently.

—Yes, Mr Bloom answered. He’s behind with Ned Lambert and Hynes.

—And Corny Kelleher himself? Mr Power asked.

—At the cemetery, Martin Cunningham said.

—I met M’Coy this morning, Mr Bloom said. He said he’d try to come.

The carriage halted short.

—What’s wrong?

—We’re stopped.

—Where are we?

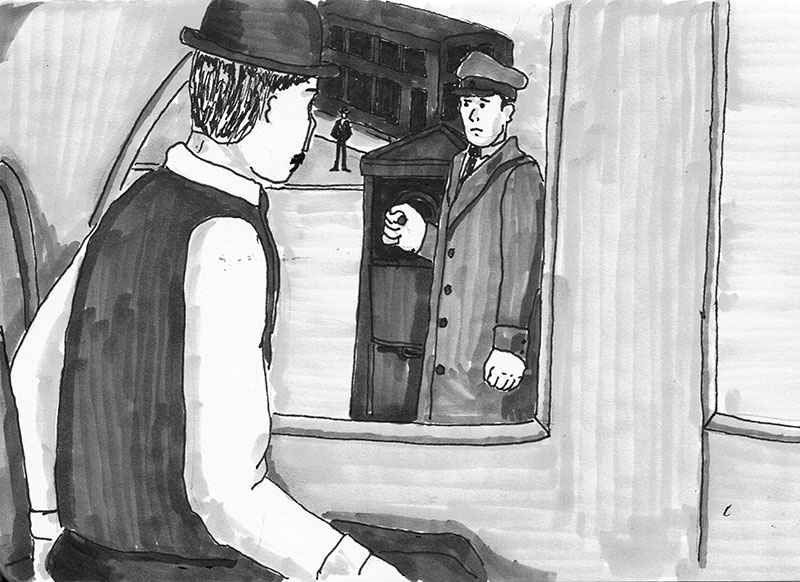

Mr Bloom put his head out of the window.

—The grand canal, he said.

Gasworks. Whooping cough they say it cures. Good job Milly never got it. Poor children! Doubles them up black and blue in convulsions. Shame really. Got off lightly with illnesses compared. Only measles. Flaxseed tea. Scarlatina, influenza epidemics. Canvassing for death. Don’t miss this chance. Dogs’ home over there. Poor old Athos! Be good to Athos, Leopold, is my last wish. Thy will be done. We obey them in the grave. A dying scrawl. He took it to heart, pined away. Quiet brute. Old men’s dogs usually are.

A raindrop spat on his hat. He drew back and saw an instant of shower spray dots over the grey flags. Apart. Curious. Like through a colander. I thought it would. My boots were creaking I remember now.

—The weather is changing, he said quietly.

—A pity it did not keep up fine, Martin Cunningham said.

—Wanted for the country, Mr Power said. There’s the sun again coming out.

Mr Dedalus, peering through his glasses towards the veiled sun, hurled a mute curse at the sky.

—It’s as uncertain as a child’s bottom, he said.

—We’re off again.

The carriage turned again its stiff wheels and their trunks swayed gently. Martin Cunningham twirled more quickly the peak of his beard.

—Tom Kernan was immense last night, he said. And Paddy Leonard taking him off to his face.

—O, draw him out, Martin, Mr Power said eagerly. Wait till you hear him, Simon, on Ben Dollard’s singing of The Croppy Boy.

—Immense, Martin Cunningham said pompously. His singing of that simple ballad, Martin, is the most trenchant rendering I ever heard in the whole course of my experience.

—Trenchant, Mr Power said laughing. He’s dead nuts on that. And the retrospective arrangement.

—Did you read Dan Dawson’s speech? Martin Cunningham asked.

—I did not then, Mr Dedalus said. Where is it?

—In the paper this morning.

Mr Bloom took the paper from his inside pocket. That book I must change for her.

—No, no, Mr Dedalus said quickly. Later on please.

Mr Bloom’s glance travelled down the edge of the paper, scanning the deaths: Callan, Coleman, Dignam, Fawcett, Lowry, Naumann, Peake, what Peake is that? is it the chap was in Crosbie and Alleyne’s? no, Sexton, Urbright. Inked characters fast fading on the frayed breaking paper. Thanks to the Little Flower. Sadly missed. To the inexpressible grief of his. Aged 88 after a long and tedious illness. Month’s mind: Quinlan. On whose soul Sweet Jesus have mercy.

It is now a month since dear Henry fled

To his home up above in the sky

While his family weeps and mourns his loss

Hoping some day to meet him on high.

I tore up the envelope? Yes. Where did I put her letter after I read it in the bath? He patted his waistcoatpocket. There all right. Dear Henry fled. Before my patience are exhausted.

National school. Meade’s yard. The hazard. Only two there now. Nodding. Full as a tick. Too much bone in their skulls. The other trotting round with a fare. An hour ago I was passing there. The jarvies raised their hats.

A pointsman’s back straightened itself upright suddenly against a tramway standard by Mr Bloom’s window. Couldn’t they invent something automatic so that the wheel itself much handier? Well but that fellow would lose his job then? Well but then another fellow would get a job making the new invention?

Antient concert rooms. Nothing on there. A man in a buff suit with a crape armlet. Not much grief there. Quarter mourning. People in law perhaps.

They went past the bleak pulpit of saint Mark’s, under the railway bridge, past the Queen’s theatre: in silence. Hoardings: Eugene Stratton, Mrs Bandmann Palmer. Could I go to see Leah tonight, I wonder. I said I. Or the Lily of Killarney? Elster Grimes Opera Company. Big powerful change. Wet bright bills for next week. Fun on the Bristol. Martin Cunningham could work a pass for the Gaiety. Have to stand a drink or two. As broad as it’s long.

He’s coming in the afternoon. Her songs.

Plasto’s. Sir Philip Crampton’s memorial fountain bust. Who was he?

—How do you do? Martin Cunningham said, raising his palm to his brow in salute.

—He doesn’t see us, Mr Power said. Yes, he does. How do you do?

—Who? Mr Dedalus asked.

—Blazes Boylan, Mr Power said. There he is airing his quiff.

Just that moment I was thinking.

Mr Dedalus bent across to salute. From the door of the Red Bank the white disc of a straw hat flashed reply: spruce figure: passed.

Mr Bloom reviewed the nails of his left hand, then those of his right hand. The nails, yes. Is there anything more in him that they she sees? Fascination. Worst man in Dublin. That keeps him alive. They sometimes feel what a person is. Instinct. But a type like that. My nails. I am just looking at them: well pared. And after: thinking alone. Body getting a bit softy. I would notice that: from remembering. What causes that? I suppose the skin can’t contract quickly enough when the flesh falls off. But the shape is there. The shape is there still. Shoulders. Hips. Plump. Night of the dance dressing. Shift stuck between the cheeks behind.

He clasped his hands between his knees and, satisfied, sent his vacant glance over their faces.

Mr Power asked:

—How is the concert tour getting on, Bloom?

—O, very well, Mr Bloom said. I hear great accounts of it. It’s a good idea, you see…

—Are you going yourself?

—Well no, Mr Bloom said. In point of fact I have to go down to the county Clare on some private business. You see the idea is to tour the chief towns. What you lose on one you can make up on the other.

—Quite so, Martin Cunningham said. Mary Anderson is up there now.

Have you good artists?

—Louis Werner is touring her, Mr Bloom said. O yes, we’ll have all topnobbers. J. C. Doyle and John MacCormack I hope and. The best, in fact.

—And Madame, Mr Power said smiling. Last but not least.

Mr Bloom unclasped his hands in a gesture of soft politeness and clasped them. Smith O’Brien. Someone has laid a bunch of flowers there. Woman. Must be his deathday. For many happy returns. The carriage wheeling by Farrell’s statue united noiselessly their unresisting knees.

Oot: a dullgarbed old man from the curbstone tendered his wares, his mouth opening: oot.

—Four bootlaces for a penny.

Wonder why he was struck off the rolls. Had his office in Hume street. Same house as Molly’s namesake, Tweedy, crown solicitor for Waterford. Has that silk hat ever since. Relics of old decency. Mourning too. Terrible comedown, poor wretch! Kicked about like snuff at a wake. O’Callaghan on his last legs.

And Madame. Twenty past eleven. Up. Mrs Fleming is in to clean. Doing her hair, humming: voglio e non vorrei. No: vorrei e non. Looking at the tips of her hairs to see if they are split. Mi trema un poco il. Beautiful on that tre her voice is: weeping tone. A thrush. A throstle. There is a word throstle that expresses that.

His eyes passed lightly over Mr Power’s goodlooking face. Greyish over the ears. Madame: smiling. I smiled back. A smile goes a long way. Only politeness perhaps. Nice fellow. Who knows is that true about the woman he keeps? Not pleasant for the wife. Yet they say, who was it told me, there is no carnal. You would imagine that would get played out pretty quick. Yes, it was Crofton met him one evening bringing her a pound of rumpsteak. What is this she was? Barmaid in Jury’s. Or the Moira, was it?

They passed under the hugecloaked Liberator’s form.

Martin Cunningham nudged Mr Power.

—Of the tribe of Reuben, he said.

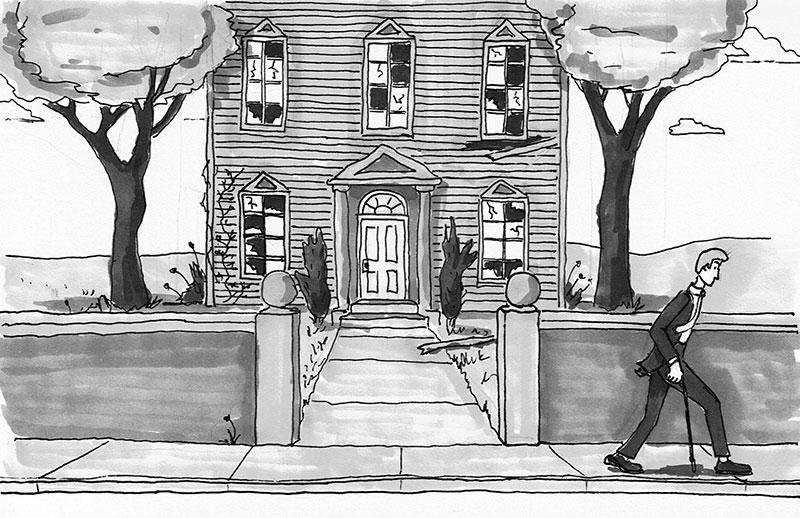

A tall blackbearded figure, bent on a stick, stumping round the corner of Elvery’s Elephant house, showed them a curved hand open on his spine.

—In all his pristine beauty, Mr Power said.

Mr Dedalus looked after the stumping figure and said mildly:

—The devil break the hasp of your back!

Mr Power, collapsing in laughter, shaded his face from the window as the carriage passed Gray’s statue.

—We have all been there, Martin Cunningham said broadly.

His eyes met Mr Bloom’s eyes. He caressed his beard, adding:

—Well, nearly all of us.

Mr Bloom began to speak with sudden eagerness to his companions’ faces.

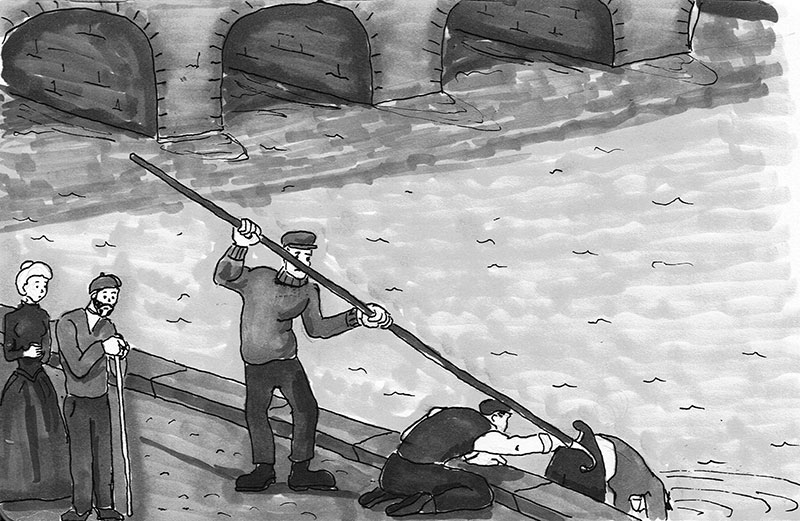

—That’s an awfully good one that’s going the rounds about Reuben J and the son.

—About the boatman? Mr Power asked.

—Yes. Isn’t it awfully good?

—What is that? Mr Dedalus asked. I didn’t hear it.

—There was a girl in the case, Mr Bloom began, and he determined to send him to the Isle of Man out of harm’s way but when they were both…..

—What? Mr Dedalus asked. That confirmed bloody hobbledehoy is it?

—Yes, Mr Bloom said. They were both on the way to the boat and he tried to drown…..

—Drown Barabbas! Mr Dedalus cried. I wish to Christ he did!

Mr Power sent a long laugh down his shaded nostrils.

—No, Mr Bloom said, the son himself…..

Martin Cunningham thwarted his speech rudely:

—Reuben J and the son were piking it down the quay next the river on their way to the Isle of Man boat and the young chiseller suddenly got loose and over the wall with him into the Liffey.

—For God’s sake! Mr Dedalus exclaimed in fright. Is he dead?

—Dead! Martin Cunningham cried. Not he! A boatman got a pole and fished him out by the slack of the breeches and he was landed up to the father on the quay more dead than alive. Half the town was there.

—Yes, Mr Bloom said. But the funny part is…..

—And Reuben J, Martin Cunningham said, gave the boatman a florin for saving his son’s life.

A stifled sigh came from under Mr Power’s hand.

—O, he did, Martin Cunningham affirmed. Like a hero. A silver florin.

—Isn’t it awfully good? Mr Bloom said eagerly.

—One and eightpence too much, Mr Dedalus said drily.

Mr Power’s choked laugh burst quietly in the carriage.

Nelson’s pillar.

—Eight plums a penny! Eight for a penny!

—We had better look a little serious, Martin Cunningham said.

Mr Dedalus sighed.

—Ah then indeed, he said, poor little Paddy wouldn’t grudge us a laugh. Many a good one he told himself.

—The Lord forgive me! Mr Power said, wiping his wet eyes with his fingers. Poor Paddy! I little thought a week ago when I saw him last and he was in his usual health that I’d be driving after him like this. He’s gone from us.

—As decent a little man as ever wore a hat, Mr Dedalus said. He went very suddenly.

—Breakdown, Martin Cunningham said. Heart.

He tapped his chest sadly.

Blazing face: redhot. Too much John Barleycorn. Cure for a red nose. Drink like the devil till it turns adelite. A lot of money he spent colouring it.

Mr Power gazed at the passing houses with rueful apprehension.

—He had a sudden death, poor fellow, he said.

—The best death, Mr Bloom said.

Their wide open eyes looked at him.

—No suffering, he said. A moment and all is over. Like dying in sleep.

No-one spoke.

Dead side of the street this. Dull business by day, land agents, temperance hotel, Falconer’s railway guide, civil service college, Gill’s, catholic club, the industrious blind. Why? Some reason. Sun or wind. At night too. Chummies and slaveys. Under the patronage of the late Father Mathew. Foundation stone for Parnell. Breakdown. Heart.

White horses with white frontlet plumes came round the Rotunda corner, galloping. A tiny coffin flashed by. In a hurry to bury. A mourning coach. Unmarried. Black for the married. Piebald for bachelors. Dun for a nun.

—Sad, Martin Cunningham said. A child.

A dwarf’s face, mauve and wrinkled like little Rudy’s was. Dwarf’s body, weak as putty, in a whitelined deal box. Burial friendly society pays. Penny a week for a sod of turf. Our. Little. Beggar. Baby. Meant nothing. Mistake of nature. If it’s healthy it’s from the mother. If not from the man. Better luck next time.

—Poor little thing, Mr Dedalus said. It’s well out of it.

The carriage climbed more slowly the hill of Rutland square. Rattle his bones. Over the stones. Only a pauper. Nobody owns.

—In the midst of life, Martin Cunningham said.

—But the worst of all, Mr Power said, is the man who takes his own life.

Martin Cunningham drew out his watch briskly, coughed and put it back.

—The greatest disgrace to have in the family, Mr Power added.

—Temporary insanity, of course, Martin Cunningham said decisively. We must take a charitable view of it.

—They say a man who does it is a coward, Mr Dedalus said.

—It is not for us to judge, Martin Cunningham said.

Mr Bloom, about to speak, closed his lips again. Martin Cunningham’s large eyes. Looking away now. Sympathetic human man he is. Intelligent. Like Shakespeare’s face. Always a good word to say. They have no mercy on that here or infanticide. Refuse christian burial. They used to drive a stake of wood through his heart in the grave. As if it wasn’t broken already. Yet sometimes they repent too late. Found in the riverbed clutching rushes. He looked at me. And that awful drunkard of a wife of his. Setting up house for her time after time and then pawning the furniture on him every Saturday almost. Leading him the life of the damned. Wear the heart out of a stone, that. Monday morning. Start afresh. Shoulder to the wheel. Lord, she must have looked a sight that night Dedalus told me he was in there. Drunk about the place and capering with Martin’s umbrella.

And they call me the jewel of Asia,

Of Asia,

The geisha.

He looked away from me. He knows. Rattle his bones.

That afternoon of the inquest. The redlabelled bottle on the table. The room in the hotel with hunting pictures. Stuffy it was. Sunlight through the slats of the Venetian blind. The coroner’s sunlit ears, big and hairy. Boots giving evidence. Thought he was asleep first. Then saw like yellow streaks on his face. Had slipped down to the foot of the bed. Verdict: overdose. Death by misadventure. The letter. For my son Leopold.

No more pain. Wake no more. Nobody owns.

The carriage rattled swiftly along Blessington street. Over the stones.

—We are going the pace, I think, Martin Cunningham said.

—God grant he doesn’t upset us on the road, Mr Power said.

—I hope not, Martin Cunningham said. That will be a great race tomorrow in Germany. The Gordon Bennett.

—Yes, by Jove, Mr Dedalus said. That will be worth seeing, faith.

As they turned into Berkeley street a streetorgan near the Basin sent over and after them a rollicking rattling song of the halls. Has anybody here seen Kelly? Kay ee double ell wy. Dead March from Saul. He’s as bad as old Antonio. He left me on my ownio. Pirouette! The Mater Misericordiae. Eccles street. My house down there. Big place. Ward for incurables there. Very encouraging. Our Lady’s Hospice for the dying. Deadhouse handy underneath. Where old Mrs Riordan died. They look terrible the women. Her feeding cup and rubbing her mouth with the spoon. Then the screen round her bed for her to die. Nice young student that was dressed that bite the bee gave me. He’s gone over to the lying-in hospital they told me. From one extreme to the other.

The carriage galloped round a corner: stopped.

—What’s wrong now?

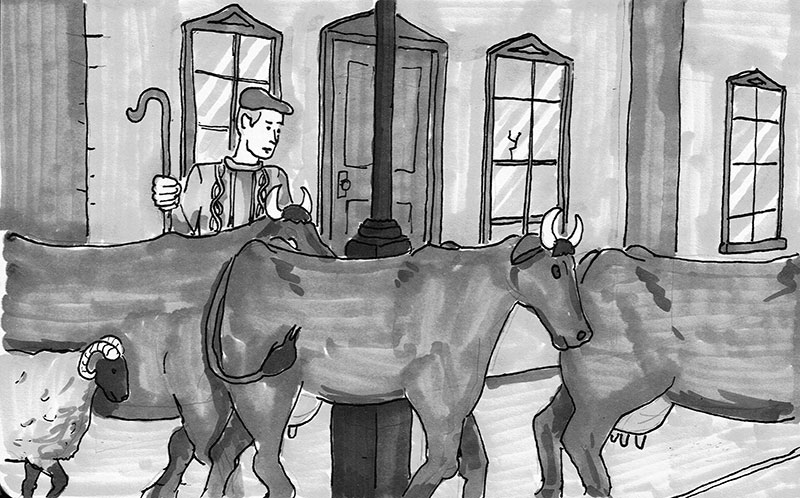

A divided drove of branded cattle passed the windows, lowing, slouching by on padded hoofs, whisking their tails slowly on their clotted bony croups. Outside them and through them ran raddled sheep bleating their fear.

—Emigrants, Mr Power said.

—Huuuh! the drover’s voice cried, his switch sounding on their flanks. Huuuh! out of that!

Thursday, of course. Tomorrow is killing day. Springers. Cuffe sold them about twentyseven quid each. For Liverpool probably. Roastbeef for old England. They buy up all the juicy ones. And then the fifth quarter lost: all that raw stuff, hide, hair, horns. Comes to a big thing in a year. Dead meat trade. Byproducts of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine. Wonder if that dodge works now getting dicky meat off the train at Clonsilla.

The carriage moved on through the drove.

—I can’t make out why the corporation doesn’t run a tramline from the parkgate to the quays, Mr Bloom said. All those animals could be taken in trucks down to the boats.

—Instead of blocking up the thoroughfare, Martin Cunningham said. Quite right. They ought to.

—Yes, Mr Bloom said, and another thing I often thought, is to have municipal funeral trams like they have in Milan, you know. Run the line out to the cemetery gates and have special trams, hearse and carriage and all. Don’t you see what I mean?

—O, that be damned for a story, Mr Dedalus said. Pullman car and saloon diningroom.

—A poor lookout for Corny, Mr Power added.

—Why? Mr Bloom asked, turning to Mr Dedalus. Wouldn’t it be more decent than galloping two abreast?

—Well, there’s something in that, Mr Dedalus granted.

—And, Martin Cunningham said, we wouldn’t have scenes like that when the hearse capsized round Dunphy’s and upset the coffin on to the road.

—That was terrible, Mr Power’s shocked face said, and the corpse fell about the road. Terrible!

—First round Dunphy’s, Mr Dedalus said, nodding. Gordon Bennett cup.

—Praises be to God! Martin Cunningham said piously.

Bom! Upset. A coffin bumped out on to the road. Burst open. Paddy Dignam shot out and rolling over stiff in the dust in a brown habit too large for him. Red face: grey now. Mouth fallen open. Asking what’s up now. Quite right to close it. Looks horrid open. Then the insides decompose quickly. Much better to close up all the orifices. Yes, also. With wax. The sphincter loose. Seal up all.

—Dunphy’s, Mr Power announced as the carriage turned right.

Dunphy’s corner. Mourning coaches drawn up, drowning their grief. A pause by the wayside. Tiptop position for a pub. Expect we’ll pull up here on the way back to drink his health. Pass round the consolation. Elixir of life.

But suppose now it did happen. Would he bleed if a nail say cut him in the knocking about? He would and he wouldn’t, I suppose. Depends on where. The circulation stops. Still some might ooze out of an artery. It would be better to bury them in red: a dark red.

In silence they drove along Phibsborough road. An empty hearse trotted by, coming from the cemetery: looks relieved.

Crossguns bridge: the royal canal.

Water rushed roaring through the sluices. A man stood on his dropping barge, between clamps of turf. On the towpath by the lock a slacktethered horse. Aboard of the Bugabu.

Their eyes watched him. On the slow weedy waterway he had floated on his raft coastward over Ireland drawn by a haulage rope past beds of reeds, over slime, mudchoked bottles, carrion dogs. Athlone, Mullingar, Moyvalley, I could make a walking tour to see Milly by the canal. Or cycle down. Hire some old crock, safety. Wren had one the other day at the auction but a lady’s. Developing waterways. James M’Cann’s hobby to row me o’er the ferry. Cheaper transit. By easy stages. Houseboats. Camping out. Also hearses. To heaven by water. Perhaps I will without writing. Come as a surprise, Leixlip, Clonsilla. Dropping down lock by lock to Dublin. With turf from the midland bogs. Salute. He lifted his brown straw hat, saluting Paddy Dignam.

They drove on past Brian Boroimhe house. Near it now.

—I wonder how is our friend Fogarty getting on, Mr Power said.

—Better ask Tom Kernan, Mr Dedalus said.

—How is that? Martin Cunningham said. Left him weeping, I suppose?

—Though lost to sight, Mr Dedalus said, to memory dear.

The carriage steered left for Finglas road.

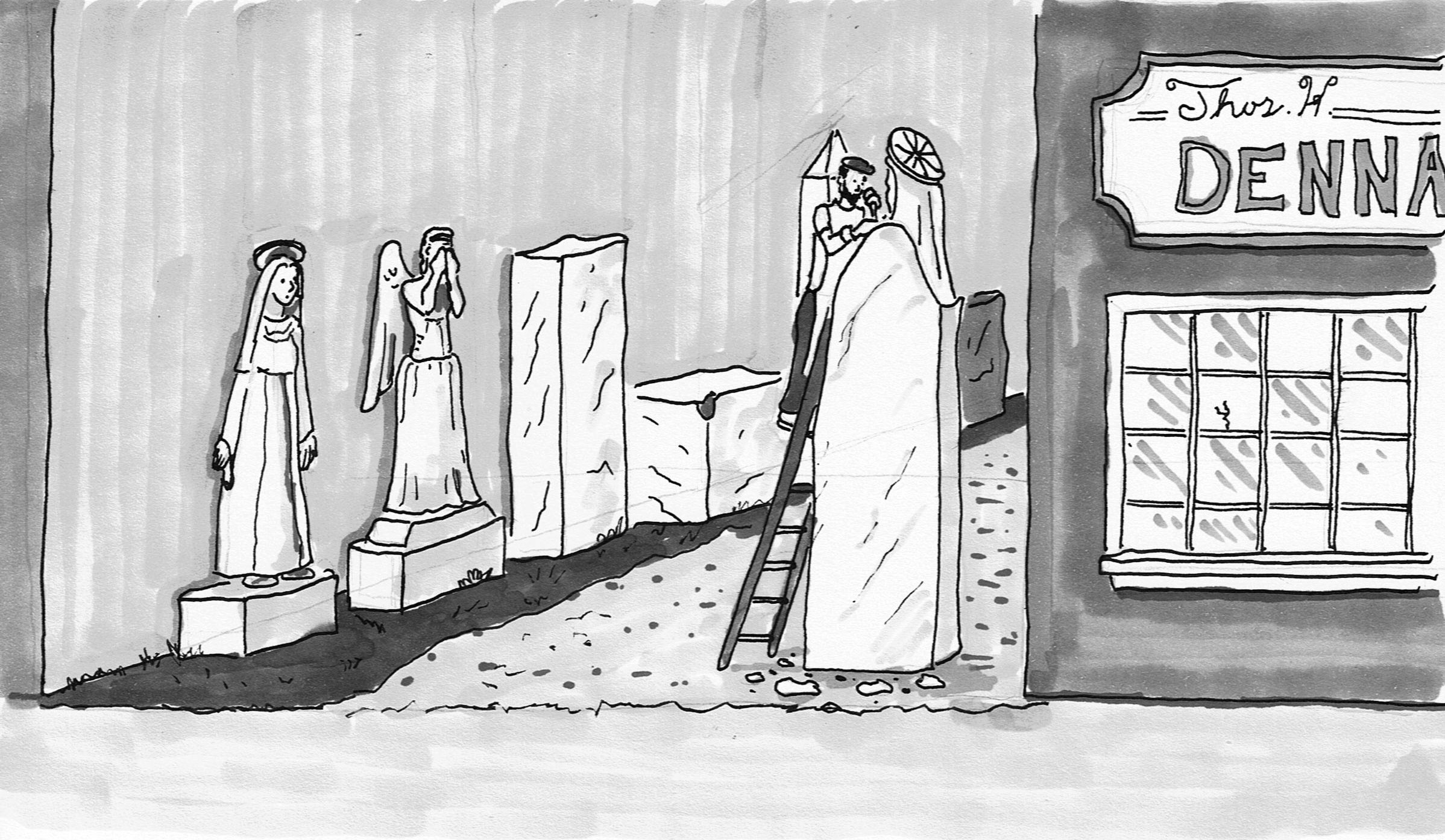

The stonecutter’s yard on the right. Last lap. Crowded on the spit of land silent shapes appeared, white, sorrowful, holding out calm hands, knelt in grief, pointing. Fragments of shapes, hewn. In white silence: appealing. The best obtainable. Thos. H. Dennany, monumental builder and sculptor.

Passed.

On the curbstone before Jimmy Geary, the sexton’s, an old tramp sat, grumbling, emptying the dirt and stones out of his huge dustbrown yawning boot. After life’s journey.

Gloomy gardens then went by: one by one: gloomy houses.

Mr Power pointed.

—That is where Childs was murdered, he said. The last house.

—So it is, Mr Dedalus said. A gruesome case. Seymour Bushe got him off. Murdered his brother. Or so they said.

—The crown had no evidence, Mr Power said.

—Only circumstantial, Martin Cunningham added. That’s the maxim of the law. Better for ninetynine guilty to escape than for one innocent person to be wrongfully condemned.

They looked. Murderer’s ground. It passed darkly. Shuttered, tenantless, unweeded garden. Whole place gone to hell. Wrongfully condemned. Murder. The murderer’s image in the eye of the murdered. They love reading about it. Man’s head found in a garden. Her clothing consisted of. How she met her death. Recent outrage. The weapon used. Murderer is still at large. Clues. A shoelace. The body to be exhumed. Murder will out.

Cramped in this carriage. She mightn’t like me to come that way without letting her know. Must be careful about women. Catch them once with their pants down. Never forgive you after. Fifteen.

The high railings of Prospect rippled past their gaze. Dark poplars, rare white forms. Forms more frequent, white shapes thronged amid the trees, white forms and fragments streaming by mutely, sustaining vain gestures on the air.

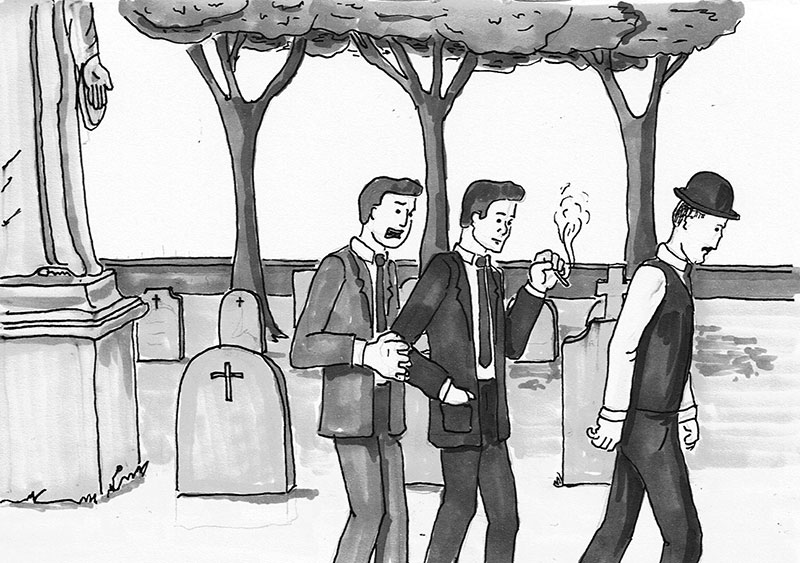

The felly harshed against the curbstone: stopped. Martin Cunningham put out his arm and, wrenching back the handle, shoved the door open with his knee. He stepped out. Mr Power and Mr Dedalus followed.

Change that soap now. Mr Bloom’s hand unbuttoned his hip pocket swiftly and transferred the paperstuck soap to his inner handkerchief pocket. He stepped out of the carriage, replacing the newspaper his other hand still held.

Paltry funeral: coach and three carriages. It’s all the same. Pallbearers, gold reins, requiem mass, firing a volley. Pomp of death. Beyond the hind carriage a hawker stood by his barrow of cakes and fruit. Simnel cakes those are, stuck together: cakes for the dead. Dogbiscuits. Who ate them? Mourners coming out.

He followed his companions. Mr Kernan and Ned Lambert followed, Hynes walking after them. Corny Kelleher stood by the opened hearse and took out the two wreaths. He handed one to the boy.

Where is that child’s funeral disappeared to?

A team of horses passed from Finglas with toiling plodding tread, dragging through the funereal silence a creaking waggon on which lay a granite block. The waggoner marching at their head saluted.

Coffin now. Got here before us, dead as he is. Horse looking round at it with his plume skeowways. Dull eye: collar tight on his neck, pressing on a bloodvessel or something. Do they know what they cart out here every day? Must be twenty or thirty funerals every day. Then Mount Jerome for the protestants. Funerals all over the world everywhere every minute. Shovelling them under by the cartload doublequick. Thousands every hour. Too many in the world.

Mourners came out through the gates: woman and a girl. Leanjawed harpy, hard woman at a bargain, her bonnet awry. Girl’s face stained with dirt and tears, holding the woman’s arm, looking up at her for a sign to cry. Fish’s face, bloodless and livid.

The mutes shouldered the coffin and bore it in through the gates. So much dead weight. Felt heavier myself stepping out of that bath. First the stiff: then the friends of the stiff. Corny Kelleher and the boy followed with their wreaths. Who is that beside them? Ah, the brother-in-law.

All walked after.

Martin Cunningham whispered:

—I was in mortal agony with you talking of suicide before Bloom.

—What? Mr Power whispered. How so?

—His father poisoned himself, Martin Cunningham whispered. Had the Queen’s hotel in Ennis. You heard him say he was going to Clare. Anniversary.

—O God! Mr Power whispered. First I heard of it. Poisoned himself?

He glanced behind him to where a face with dark thinking eyes followed towards the cardinal’s mausoleum. Speaking.

—Was he insured? Mr Bloom asked.

—I believe so, Mr Kernan answered. But the policy was heavily mortgaged. Martin is trying to get the youngster into Artane.

—How many children did he leave?

—Five. Ned Lambert says he’ll try to get one of the girls into Todd’s.

—A sad case, Mr Bloom said gently. Five young children.

—A great blow to the poor wife, Mr Kernan added.

—Indeed yes, Mr Bloom agreed.

Has the laugh at him now.

He looked down at the boots he had blacked and polished. She had outlived him. Lost her husband. More dead for her than for me. One must outlive the other. Wise men say. There are more women than men in the world. Condole with her. Your terrible loss. I hope you’ll soon follow him. For Hindu widows only. She would marry another. Him? No. Yet who knows after. Widowhood not the thing since the old queen died. Drawn on a guncarriage. Victoria and Albert. Frogmore memorial mourning. But in the end she put a few violets in her bonnet. Vain in her heart of hearts. All for a shadow. Consort not even a king. Her son was the substance. Something new to hope for not like the past she wanted back, waiting. It never comes. One must go first: alone, under the ground: and lie no more in her warm bed.

—How are you, Simon? Ned Lambert said softly, clasping hands. Haven’t seen you for a month of Sundays.

—Never better. How are all in Cork’s own town?

—I was down there for the Cork park races on Easter Monday, Ned Lambert said. Same old six and eightpence. Stopped with Dick Tivy.

—And how is Dick, the solid man?

—Nothing between himself and heaven, Ned Lambert answered.

—By the holy Paul! Mr Dedalus said in subdued wonder. Dick Tivy bald?

—Martin is going to get up a whip for the youngsters, Ned Lambert said, pointing ahead. A few bob a skull. Just to keep them going till the insurance is cleared up.

—Yes, yes, Mr Dedalus said dubiously. Is that the eldest boy in front?

—Yes, Ned Lambert said, with the wife’s brother. John Henry Menton is behind. He put down his name for a quid.

—I’ll engage he did, Mr Dedalus said. I often told poor Paddy he ought to mind that job. John Henry is not the worst in the world.

—How did he lose it? Ned Lambert asked. Liquor, what?

—Many a good man’s fault, Mr Dedalus said with a sigh.

They halted about the door of the mortuary chapel. Mr Bloom stood behind the boy with the wreath looking down at his sleekcombed hair and at the slender furrowed neck inside his brandnew collar. Poor boy! Was he there when the father? Both unconscious. Lighten up at the last moment and recognise for the last time. All he might have done. I owe three shillings to O’Grady. Would he understand? The mutes bore the coffin into the chapel. Which end is his head?

After a moment he followed the others in, blinking in the screened light. The coffin lay on its bier before the chancel, four tall yellow candles at its corners. Always in front of us. Corny Kelleher, laying a wreath at each fore corner, beckoned to the boy to kneel. The mourners knelt here and there in prayingdesks. Mr Bloom stood behind near the font and, when all had knelt, dropped carefully his unfolded newspaper from his pocket and knelt his right knee upon it. He fitted his black hat gently on his left knee and, holding its brim, bent over piously.

A server bearing a brass bucket with something in it came out through a door. The whitesmocked priest came after him, tidying his stole with one hand, balancing with the other a little book against his toad’s belly. Who’ll read the book? I, said the rook.

They halted by the bier and the priest began to read out of his book with a fluent croak.

Father Coffey. I knew his name was like a coffin. Dominenamine. Bully about the muzzle he looks. Bosses the show. Muscular christian. Woe betide anyone that looks crooked at him: priest. Thou art Peter. Burst sideways like a sheep in clover Dedalus says he will. With a belly on him like a poisoned pup. Most amusing expressions that man finds. Hhhn: burst sideways.

—Non intres in judicium cum servo tuo, Domine.

Makes them feel more important to be prayed over in Latin. Requiem mass. Crape weepers. Blackedged notepaper. Your name on the altarlist. Chilly place this. Want to feed well, sitting in there all the morning in the gloom kicking his heels waiting for the next please. Eyes of a toad too. What swells him up that way? Molly gets swelled after cabbage. Air of the place maybe. Looks full up of bad gas. Must be an infernal lot of bad gas round the place. Butchers, for instance: they get like raw beefsteaks. Who was telling me? Mervyn Browne. Down in the vaults of saint Werburgh’s lovely old organ hundred and fifty they have to bore a hole in the coffins sometimes to let out the bad gas and burn it. Out it rushes: blue. One whiff of that and you’re a goner.

My kneecap is hurting me. Ow. That’s better.

The priest took a stick with a knob at the end of it out of the boy’s bucket and shook it over the coffin. Then he walked to the other end and shook it again. Then he came back and put it back in the bucket. As you were before you rested. It’s all written down: he has to do it.

—Et ne nos inducas in tentationem.

The server piped the answers in the treble. I often thought it would be better to have boy servants. Up to fifteen or so. After that, of course …

Holy water that was, I expect. Shaking sleep out of it. He must be fed up with that job, shaking that thing over all the corpses they trot up. What harm if he could see what he was shaking it over. Every mortal day a fresh batch: middleaged men, old women, children, women dead in childbirth, men with beards, baldheaded businessmen, consumptive girls with little sparrows’ breasts. All the year round he prayed the same thing over them all and shook water on top of them: sleep. On Dignam now.

—In paradisum.

Said he was going to paradise or is in paradise. Says that over everybody. Tiresome kind of a job. But he has to say something.

The priest closed his book and went off, followed by the server. Corny Kelleher opened the sidedoors and the gravediggers came in, hoisted the coffin again, carried it out and shoved it on their cart. Corny Kelleher gave one wreath to the boy and one to the brother-in-law. All followed them out of the sidedoors into the mild grey air. Mr Bloom came last folding his paper again into his pocket. He gazed gravely at the ground till the coffincart wheeled off to the left. The metal wheels ground the gravel with a sharp grating cry and the pack of blunt boots followed the trundled barrow along a lane of sepulchres.

The ree the ra the ree the ra the roo. Lord, I mustn’t lilt here.

—The O’Connell circle, Mr Dedalus said about him.

Mr Power’s soft eyes went up to the apex of the lofty cone.

—He’s at rest, he said, in the middle of his people, old Dan O’. But his heart is buried in Rome. How many broken hearts are buried here, Simon!

—Her grave is over there, Jack, Mr Dedalus said. I’ll soon be stretched beside her. Let Him take me whenever He likes.

Breaking down, he began to weep to himself quietly, stumbling a little in his walk. Mr Power took his arm.

—She’s better where she is, he said kindly.

—I suppose so, Mr Dedalus said with a weak gasp. I suppose she is in heaven if there is a heaven.

Corny Kelleher stepped aside from his rank and allowed the mourners to plod by.

—Sad occasions, Mr Kernan began politely.

Mr Bloom closed his eyes and sadly twice bowed his head.

—The others are putting on their hats, Mr Kernan said. I suppose we can do so too. We are the last. This cemetery is a treacherous place.

They covered their heads.

—The reverend gentleman read the service too quickly, don’t you think? Mr Kernan said with reproof.

Mr Bloom nodded gravely looking in the quick bloodshot eyes. Secret eyes, secretsearching. Mason, I think: not sure. Beside him again. We are the last. In the same boat. Hope he’ll say something else.

Mr Kernan added:

—The service of the Irish church used in Mount Jerome is simpler, more impressive I must say.

Mr Bloom gave prudent assent. The language of course was another thing.

Mr Kernan said with solemnity:

—I am the resurrection and the life. That touches a man’s inmost heart.

—It does, Mr Bloom said.

Your heart perhaps but what price the fellow in the six feet by two with his toes to the daisies? No touching that. Seat of the affections. Broken heart. A pump after all, pumping thousands of gallons of blood every day. One fine day it gets bunged up: and there you are. Lots of them lying around here: lungs, hearts, livers. Old rusty pumps: damn the thing else. The resurrection and the life. Once you are dead you are dead. That last day idea. Knocking them all up out of their graves. Come forth, Lazarus! And he came fifth and lost the job. Get up! Last day! Then every fellow mousing around for his liver and his lights and the rest of his traps. Find damn all of himself that morning. Pennyweight of powder in a skull. Twelve grammes one pennyweight. Troy measure.

Corny Kelleher fell into step at their side.

—Everything went off A1, he said. What?

He looked on them from his drawling eye. Policeman’s shoulders. With your tooraloom tooraloom.

—As it should be, Mr Kernan said.

—What? Eh? Corny Kelleher said.

Mr Kernan assured him.

—Who is that chap behind with Tom Kernan? John Henry Menton asked. I know his face.

Ned Lambert glanced back.

—Bloom, he said, Madame Marion Tweedy that was, is, I mean, the soprano. She’s his wife.

—O, to be sure, John Henry Menton said. I haven’t seen her for some time. She was a finelooking woman. I danced with her, wait, fifteen seventeen golden years ago, at Mat Dillon’s in Roundtown. And a good armful she was.

He looked behind through the others.

—What is he? he asked. What does he do? Wasn’t he in the stationery line? I fell foul of him one evening, I remember, at bowls.

Ned Lambert smiled.

—Yes, he was, he said, in Wisdom Hely’s. A traveller for blottingpaper.

—In God’s name, John Henry Menton said, what did she marry a coon like that for? She had plenty of game in her then.

—Has still, Ned Lambert said. He does some canvassing for ads.

John Henry Menton’s large eyes stared ahead.

The barrow turned into a side lane. A portly man, ambushed among the grasses, raised his hat in homage. The gravediggers touched their caps.

—John O’Connell, Mr Power said pleased. He never forgets a friend.

Mr O’Connell shook all their hands in silence. Mr Dedalus said:

—I am come to pay you another visit.

—My dear Simon, the caretaker answered in a low voice. I don’t want your custom at all.

Saluting Ned Lambert and John Henry Menton he walked on at Martin Cunningham’s side puzzling two long keys at his back.

—Did you hear that one, he asked them, about Mulcahy from the Coombe?

—I did not, Martin Cunningham said.

They bent their silk hats in concert and Hynes inclined his ear. The caretaker hung his thumbs in the loops of his gold watchchain and spoke in a discreet tone to their vacant smiles.

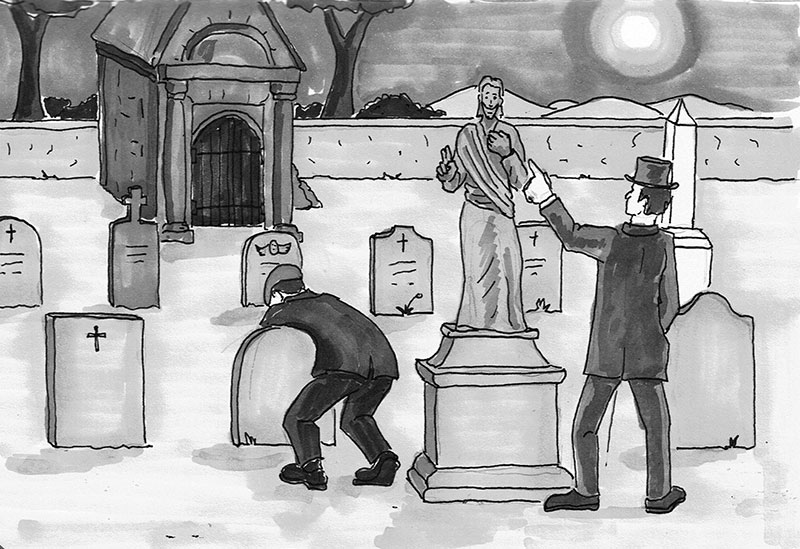

—They tell the story, he said, that two drunks came out here one foggy evening to look for the grave of a friend of theirs. They asked for Mulcahy from the Coombe and were told where he was buried. After traipsing about in the fog they found the grave sure enough. One of the drunks spelt out the name: Terence Mulcahy. The other drunk was blinking up at a statue of Our Saviour the widow had got put up.

The caretaker blinked up at one of the sepulchres they passed. He resumed:

—And, after blinking up at the sacred figure, Not a bloody bit like the man, says he. That’s not Mulcahy, says he, whoever done it.

Rewarded by smiles he fell back and spoke with Corny Kelleher, accepting the dockets given him, turning them over and scanning them as he walked.

—That’s all done with a purpose, Martin Cunningham explained to Hynes.

—I know, Hynes said. I know that.

—To cheer a fellow up, Martin Cunningham said. It’s pure goodheartedness: damn the thing else.

Mr Bloom admired the caretaker’s prosperous bulk. All want to be on good terms with him. Decent fellow, John O’Connell, real good sort. Keys: like Keyes’s ad: no fear of anyone getting out. No passout checks. Habeas corpus. I must see about that ad after the funeral. Did I write Ballsbridge on the envelope I took to cover when she disturbed me writing to Martha? Hope it’s not chucked in the dead letter office. Be the better of a shave. Grey sprouting beard. That’s the first sign when the hairs come out grey. And temper getting cross. Silver threads among the grey. Fancy being his wife. Wonder he had the gumption to propose to any girl. Come out and live in the graveyard. Dangle that before her. It might thrill her first. Courting death. Shades of night hovering here with all the dead stretched about. The shadows of the tombs when churchyards yawn and Daniel O’Connell must be a descendant I suppose who is this used to say he was a queer breedy man great catholic all the same like a big giant in the dark. Will o’ the wisp. Gas of graves. Want to keep her mind off it to conceive at all. Women especially are so touchy. Tell her a ghost story in bed to make her sleep. Have you ever seen a ghost? Well, I have. It was a pitchdark night. The clock was on the stroke of twelve. Still they’d kiss all right if properly keyed up. Whores in Turkish graveyards. Learn anything if taken young. You might pick up a young widow here. Men like that. Love among the tombstones. Romeo. Spice of pleasure. In the midst of death we are in life. Both ends meet. Tantalising for the poor dead. Smell of grilled beefsteaks to the starving. Gnawing their vitals. Desire to grig people. Molly wanting to do it at the window. Eight children he has anyway.

He has seen a fair share go under in his time, lying around him field after field. Holy fields. More room if they buried them standing. Sitting or kneeling you couldn’t. Standing? His head might come up some day above ground in a landslip with his hand pointing. All honeycombed the ground must be: oblong cells. And very neat he keeps it too: trim grass and edgings. His garden Major Gamble calls Mount Jerome. Well, so it is. Ought to be flowers of sleep. Chinese cemeteries with giant poppies growing produce the best opium Mastiansky told me. The Botanic Gardens are just over there. It’s the blood sinking in the earth gives new life. Same idea those jews they said killed the christian boy. Every man his price. Well preserved fat corpse, gentleman, epicure, invaluable for fruit garden. A bargain. By carcass of William Wilkinson, auditor and accountant, lately deceased, three pounds thirteen and six. With thanks.

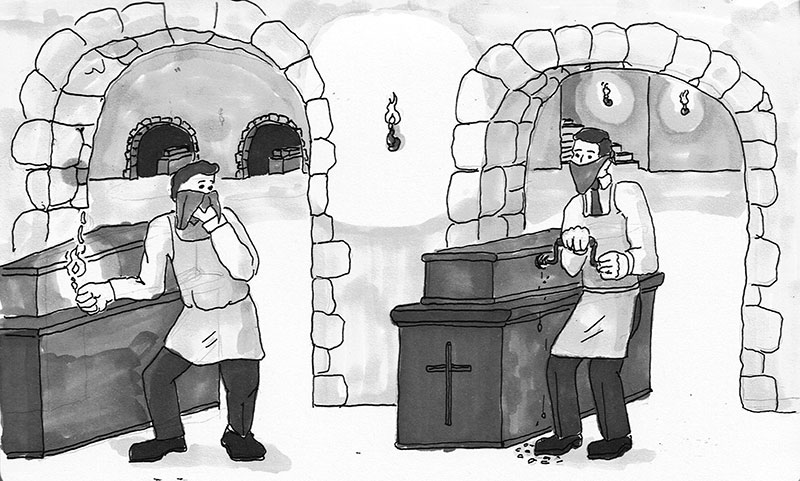

I daresay the soil would be quite fat with corpsemanure, bones, flesh, nails. Charnelhouses. Dreadful. Turning green and pink decomposing. Rot quick in damp earth. The lean old ones tougher. Then a kind of a tallowy kind of a cheesy. Then begin to get black, black treacle oozing out of them. Then dried up. Deathmoths. Of course the cells or whatever they are go on living. Changing about. Live for ever practically. Nothing to feed on feed on themselves.

But they must breed a devil of a lot of maggots. Soil must be simply swirling with them. Your head it simply swurls. Those pretty little seaside gurls. He looks cheerful enough over it. Gives him a sense of power seeing all the others go under first. Wonder how he looks at life. Cracking his jokes too: warms the cockles of his heart. The one about the bulletin. Spurgeon went to heaven 4 a.m. this morning. 11 p.m. (closing time). Not arrived yet. Peter. The dead themselves the men anyhow would like to hear an odd joke or the women to know what’s in fashion. A juicy pear or ladies’ punch, hot, strong and sweet. Keep out the damp. You must laugh sometimes so better do it that way. Gravediggers in Hamlet. Shows the profound knowledge of the human heart. Daren’t joke about the dead for two years at least. De mortuis nil nisi prius. Go out of mourning first. Hard to imagine his funeral. Seems a sort of a joke. Read your own obituary notice they say you live longer. Gives you second wind. New lease of life.

—How many have you for tomorrow? the caretaker asked.

—Two, Corny Kelleher said. Half ten and eleven.

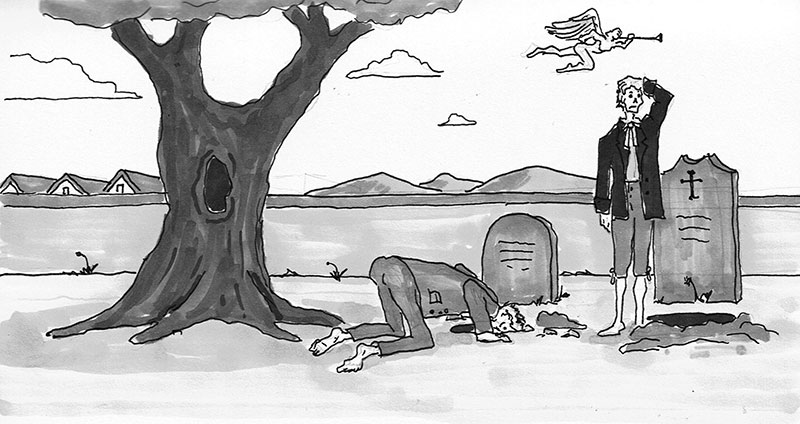

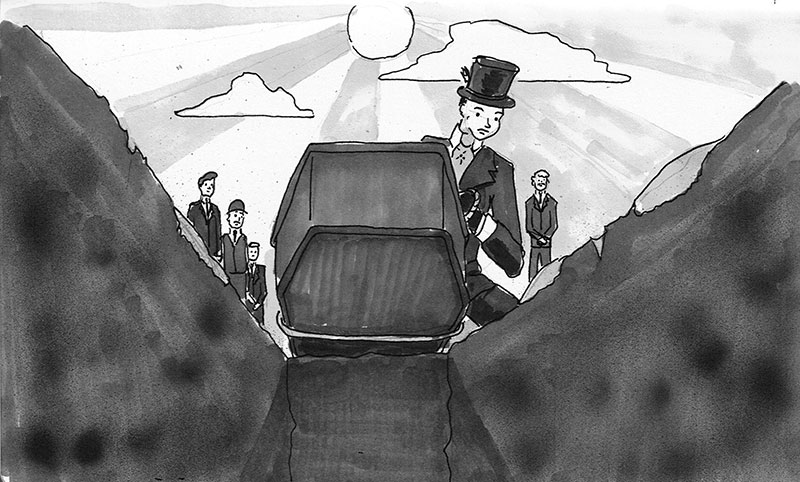

The caretaker put the papers in his pocket. The barrow had ceased to trundle. The mourners split and moved to each side of the hole, stepping with care round the graves. The gravediggers bore the coffin and set its nose on the brink, looping the bands round it.

Burying him. We come to bury Cæsar. His ides of March or June. He doesn’t know who is here nor care. Now who is that lankylooking galoot over there in the macintosh? Now who is he I’d like to know? Now I’d give a trifle to know who he is. Always someone turns up you never dreamt of. A fellow could live on his lonesome all his life. Yes, he could. Still he’d have to get someone to sod him after he died though he could dig his own grave. We all do. Only man buries. No, ants too. First thing strikes anybody. Bury the dead. Say Robinson Crusoe was true to life. Well then Friday buried him. Every Friday buries a Thursday if you come to look at it.

O, poor Robinson Crusoe!

How could you possibly do so?

Poor Dignam! His last lie on the earth in his box. When you think of them all it does seem a waste of wood. All gnawed through. They could invent a handsome bier with a kind of panel sliding, let it down that way. Ay but they might object to be buried out of another fellow’s. They’re so particular. Lay me in my native earth. Bit of clay from the holy land. Only a mother and deadborn child ever buried in the one coffin. I see what it means. I see. To protect him as long as possible even in the earth. The Irishman’s house is his coffin. Embalming in catacombs, mummies the same idea.

Mr Bloom stood far back, his hat in his hand, counting the bared heads. Twelve. I’m thirteen. No. The chap in the macintosh is thirteen. Death’s number. Where the deuce did he pop out of? He wasn’t in the chapel, that I’ll swear. Silly superstition that about thirteen.

Nice soft tweed Ned Lambert has in that suit. Tinge of purple. I had one like that when we lived in Lombard street west. Dressy fellow he was once. Used to change three suits in the day. Must get that grey suit of mine turned by Mesias. Hello. It’s dyed. His wife I forgot he’s not married or his landlady ought to have picked out those threads for him.

The coffin dived out of sight, eased down by the men straddled on the gravetrestles. They struggled up and out: and all uncovered. Twenty.

Pause.

If we were all suddenly somebody else.

Far away a donkey brayed. Rain. No such ass. Never see a dead one, they say. Shame of death. They hide. Also poor papa went away.

Gentle sweet air blew round the bared heads in a whisper. Whisper. The boy by the gravehead held his wreath with both hands staring quietly in the black open space. Mr Bloom moved behind the portly kindly caretaker. Wellcut frockcoat. Weighing them up perhaps to see which will go next. Well, it is a long rest. Feel no more. It’s the moment you feel. Must be damned unpleasant. Can’t believe it at first. Mistake must be: someone else. Try the house opposite. Wait, I wanted to. I haven’t yet. Then darkened deathchamber. Light they want. Whispering around you. Would you like to see a priest? Then rambling and wandering. Delirium all you hid all your life. The death struggle. His sleep is not natural. Press his lower eyelid. Watching is his nose pointed is his jaw sinking are the soles of his feet yellow. Pull the pillow away and finish it off on the floor since he’s doomed. Devil in that picture of sinner’s death showing him a woman. Dying to embrace her in his shirt. Last act of Lucia. Shall I nevermore behold thee? Bam! He expires. Gone at last. People talk about you a bit: forget you. Don’t forget to pray for him. Remember him in your prayers. Even Parnell. Ivy day dying out. Then they follow: dropping into a hole, one after the other.

We are praying now for the repose of his soul. Hoping you’re well and not in hell. Nice change of air. Out of the fryingpan of life into the fire of purgatory.

Does he ever think of the hole waiting for himself? They say you do when you shiver in the sun. Someone walking over it. Callboy’s warning. Near you. Mine over there towards Finglas, the plot I bought. Mamma, poor mamma, and little Rudy.

The gravediggers took up their spades and flung heavy clods of clay in on the coffin. Mr Bloom turned away his face. And if he was alive all the time? Whew! By jingo, that would be awful! No, no: he is dead, of course. Of course he is dead. Monday he died. They ought to have some law to pierce the heart and make sure or an electric clock or a telephone in the coffin and some kind of a canvas airhole. Flag of distress. Three days. Rather long to keep them in summer. Just as well to get shut of them as soon as you are sure there’s no.

The clay fell softer. Begin to be forgotten. Out of sight, out of mind.

The caretaker moved away a few paces and put on his hat. Had enough of it. The mourners took heart of grace, one by one, covering themselves without show. Mr Bloom put on his hat and saw the portly figure make its way deftly through the maze of graves. Quietly, sure of his ground, he traversed the dismal fields.

Hynes jotting down something in his notebook. Ah, the names. But he knows them all. No: coming to me.

—I am just taking the names, Hynes said below his breath. What is your christian name? I’m not sure.

—L, Mr Bloom said. Leopold. And you might put down M’Coy’s name too. He asked me to.

—Charley, Hynes said writing. I know. He was on the Freeman once.

So he was before he got the job in the morgue under Louis Byrne. Good idea a postmortem for doctors. Find out what they imagine they know. He died of a Tuesday. Got the run. Levanted with the cash of a few ads. Charley, you’re my darling. That was why he asked me to. O well, does no harm. I saw to that, M’Coy. Thanks, old chap: much obliged. Leave him under an obligation: costs nothing.

—And tell us, Hynes said, do you know that fellow in the, fellow was over there in the…

He looked around.

—Macintosh. Yes, I saw him, Mr Bloom said. Where is he now?

—M’Intosh, Hynes said scribbling. I don’t know who he is. Is that his name?

He moved away, looking about him.

—No, Mr Bloom began, turning and stopping. I say, Hynes!

Didn’t hear. What? Where has he disappeared to? Not a sign. Well of all the. Has anybody here seen? Kay ee double ell. Become invisible. Good Lord, what became of him?

A seventh gravedigger came beside Mr Bloom to take up an idle spade.

—O, excuse me!

He stepped aside nimbly.

Clay, brown, damp, began to be seen in the hole. It rose. Nearly over. A mound of damp clods rose more, rose, and the gravediggers rested their spades. All uncovered again for a few instants. The boy propped his wreath against a corner: the brother-in-law his on a lump. The gravediggers put on their caps and carried their earthy spades towards the barrow. Then knocked the blades lightly on the turf: clean. One bent to pluck from the haft a long tuft of grass. One, leaving his mates, walked slowly on with shouldered weapon, its blade blueglancing. Silently at the gravehead another coiled the coffinband. His navelcord. The brother-in-law, turning away, placed something in his free hand. Thanks in silence. Sorry, sir: trouble. Headshake. I know that. For yourselves just.

The mourners moved away slowly without aim, by devious paths, staying at whiles to read a name on a tomb.

—Let us go round by the chief’s grave, Hynes said. We have time.

—Let us, Mr Power said.

They turned to the right, following their slow thoughts. With awe Mr Power’s blank voice spoke:

—Some say he is not in that grave at all. That the coffin was filled with stones. That one day he will come again.

Hynes shook his head.

—Parnell will never come again, he said. He’s there, all that was mortal of him. Peace to his ashes.

Mr Bloom walked unheeded along his grove by saddened angels, crosses, broken pillars, family vaults, stone hopes praying with upcast eyes, old Ireland’s hearts and hands. More sensible to spend the money on some charity for the living. Pray for the repose of the soul of. Does anybody really? Plant him and have done with him. Like down a coalshoot. Then lump them together to save time. All souls’ day. Twentyseventh I’ll be at his grave. Ten shillings for the gardener. He keeps it free of weeds. Old man himself. Bent down double with his shears clipping. Near death’s door. Who passed away. Who departed this life. As if they did it of their own accord. Got the shove, all of them. Who kicked the bucket. More interesting if they told you what they were. So and So, wheelwright. I travelled for cork lino. I paid five shillings in the pound. Or a woman’s with her saucepan. I cooked good Irish stew. Eulogy in a country churchyard it ought to be that poem of whose is it Wordsworth or Thomas Campbell. Entered into rest the protestants put it. Old Dr Murren’s. The great physician called him home. Well it’s God’s acre for them. Nice country residence. Newly plastered and painted. Ideal spot to have a quiet smoke and read the Church Times. Marriage ads they never try to beautify. Rusty wreaths hung on knobs, garlands of bronzefoil. Better value that for the money. Still, the flowers are more poetical. The other gets rather tiresome, never withering. Expresses nothing. Immortelles.

A bird sat tamely perched on a poplar branch. Like stuffed. Like the wedding present alderman Hooper gave us. Hoo! Not a budge out of him. Knows there are no catapults to let fly at him. Dead animal even sadder. Silly-Milly burying the little dead bird in the kitchen matchbox, a daisychain and bits of broken chainies on the grave.

The Sacred Heart that is: showing it. Heart on his sleeve. Ought to be sideways and red it should be painted like a real heart. Ireland was dedicated to it or whatever that. Seems anything but pleased. Why this infliction? Would birds come then and peck like the boy with the basket of fruit but he said no because they ought to have been afraid of the boy. Apollo that was.

How many! All these here once walked round Dublin. Faithful departed. As you are now so once were we.

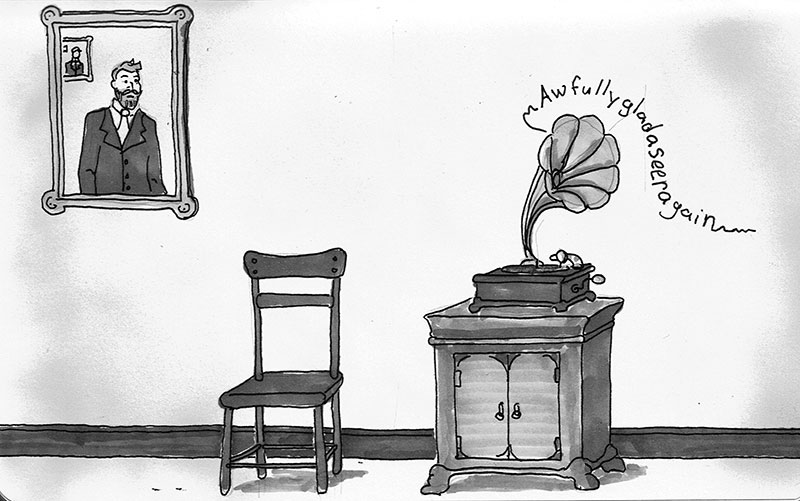

Besides how could you remember everybody? Eyes, walk, voice. Well, the voice, yes: gramophone. Have a gramophone in every grave or keep it in the house. After dinner on a Sunday. Put on poor old greatgrandfather. Kraahraark! Hellohellohello amawfullyglad kraark awfullygladaseeagain hellohello amawf krpthsth. Remind you of the voice like the photograph reminds you of the face. Otherwise you couldn’t remember the face after fifteen years, say. For instance who? For instance some fellow that died when I was in Wisdom Hely’s.

Rtststr! A rattle of pebbles. Wait. Stop!

He looked down intently into a stone crypt. Some animal. Wait. There he goes.

An obese grey rat toddled along the side of the crypt, moving the pebbles. An old stager: greatgrandfather: he knows the ropes. The grey alive crushed itself in under the plinth, wriggled itself in under it. Good hidingplace for treasure.

Who lives there? Are laid the remains of Robert Emery. Robert Emmet was buried here by torchlight, wasn’t he? Making his rounds.

Tail gone now.

One of those chaps would make short work of a fellow. Pick the bones clean no matter who it was. Ordinary meat for them. A corpse is meat gone bad. Well and what’s cheese? Corpse of milk. I read in that Voyages in China that the Chinese say a white man smells like a corpse. Cremation better. Priests dead against it. Devilling for the other firm. Wholesale burners and Dutch oven dealers. Time of the plague. Quicklime feverpits to eat them. Lethal chamber. Ashes to ashes. Or bury at sea. Where is that Parsee tower of silence? Eaten by birds. Earth, fire, water. Drowning they say is the pleasantest. See your whole life in a flash. But being brought back to life no. Can’t bury in the air however. Out of a flying machine. Wonder does the news go about whenever a fresh one is let down. Underground communication. We learned that from them. Wouldn’t be surprised. Regular square feed for them. Flies come before he’s well dead. Got wind of Dignam. They wouldn’t care about the smell of it. Saltwhite crumbling mush of corpse: smell, taste like raw white turnips.

The gates glimmered in front: still open. Back to the world again. Enough of this place. Brings you a bit nearer every time. Last time I was here was Mrs Sinico’s funeral. Poor papa too. The love that kills. And even scraping up the earth at night with a lantern like that case I read of to get at fresh buried females or even putrefied with running gravesores. Give you the creeps after a bit. I will appear to you after death. You will see my ghost after death. My ghost will haunt you after death. There is another world after death named hell. I do not like that other world she wrote. No more do I. Plenty to see and hear and feel yet. Feel live warm beings near you. Let them sleep in their maggoty beds. They are not going to get me this innings. Warm beds: warm fullblooded life.

Martin Cunningham emerged from a sidepath, talking gravely.

Solicitor, I think. I know his face. Menton, John Henry, solicitor, commissioner for oaths and affidavits. Dignam used to be in his office. Mat Dillon’s long ago. Jolly Mat. Convivial evenings. Cold fowl, cigars, the Tantalus glasses. Heart of gold really. Yes, Menton. Got his rag out that evening on the bowlinggreen because I sailed inside him. Pure fluke of mine: the bias. Why he took such a rooted dislike to me. Hate at first sight. Molly and Floey Dillon linked under the lilactree, laughing. Fellow always like that, mortified if women are by.

Got a dinge in the side of his hat. Carriage probably.

—Excuse me, sir, Mr Bloom said beside them.

They stopped.

—Your hat is a little crushed, Mr Bloom said pointing.

John Henry Menton stared at him for an instant without moving.

—There, Martin Cunningham helped, pointing also.

John Henry Menton took off his hat, bulged out the dinge and smoothed the nap with care on his coatsleeve. He clapped the hat on his head again.

—It’s all right now, Martin Cunningham said.

John Henry Menton jerked his head down in acknowledgment.

—Thank you, he said shortly.

They walked on towards the gates. Mr Bloom, chapfallen, drew behind a few paces so as not to overhear. Martin laying down the law. Martin could wind a sappyhead like that round his little finger, without his seeing it.

Oyster eyes. Never mind. Be sorry after perhaps when it dawns on him. Get the pull over him that way.

Thank you. How grand we are this morning!