We idolize sincerity in others because we suffer from a cultural phobia that others won’t think we’re good enough. The self-help industry plays into that fear as new self-improvement books clog magazine racks at supermarket check-out lines. TV is rife with droning infomercials wherein C-list celebrities with unnaturally white teeth smugly advise how best to repair our sad and ruined lives. Legions of self-appointed personal life coaches cold-call cell phone lists seemingly at random, seeking unsuspecting victims for “mentoring.” As a society we spend billions on self-improvement products.

We idolize sincerity in others because we suffer from a cultural phobia that others won’t think we’re good enough. The self-help industry plays into that fear as new self-improvement books clog magazine racks at supermarket check-out lines. TV is rife with droning infomercials wherein C-list celebrities with unnaturally white teeth smugly advise how best to repair our sad and ruined lives. Legions of self-appointed personal life coaches cold-call cell phone lists seemingly at random, seeking unsuspecting victims for “mentoring.” As a society we spend billions on self-improvement products.

But should we? Spin-doctoring celebrity publicists discovered in the 1990’s they could hit the reset-button on a celebrity’s credibility by issuing a public confession to some “addiction” and hide the offender for a few weeks in the magical land of “rehab” (where happiness rains down like gumdrops and washes all sins away). Some return as freshly-repentant lifestyle gurus, dispensing their new wisdom to the consumer public. Really? They tried to make Amy Winehouse go to rehab and she said no, no, no. Then her career stalled and she said yes, yes, yes. They pronounced her cured, but now she’s dead, dead, dead. Was she EVER qualified to advise anyone how to live a successful life? Is 50 Cent? Or even (good lord) Kirstie Alley? How is that different from seriously listening to a hygenically-challenged panhandler on the Las Vegas strip as he offers to divulge his “can’t-be-beat” Keno system for enough change to buy a bottle of Ripple? Or stringently obeying the dubious instructions of a droopy-lidded, cigarette-stained, card-reading psychic in a dingy back room behind an old laundromat as she explains how to achieve perfect success in life and love by wearing a hand-made charm she sells for 20 bucks? Let’s face it: if there really are any ultra-skilled financial geniuses or successful psychics on the planet we already know their names, because Forbes lists them every year on their annual Billionaire list.

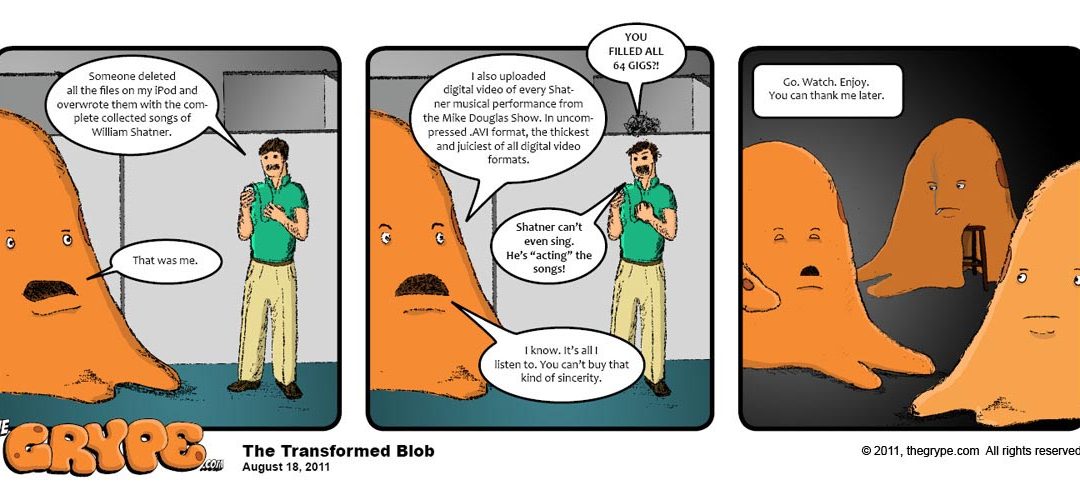

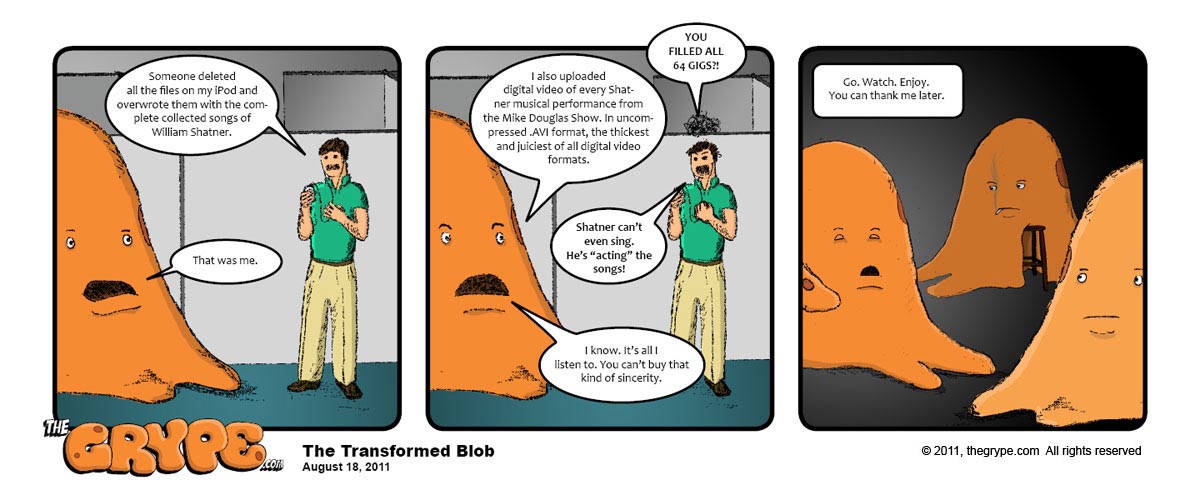

Sincerity is easy to fake. We might outwardly chuckle at it and assume it must be some campy inside joke— the deadpan stoicism of Adam West— but we still admire it if we can’t find a crack in it, out of grudging respect for the purity of innocent self-confidence in the face of external cynicism— as in the songsmithing of William Shatner. We secretly admire Shatner NOT because he is “playing” the straight man; but because he IS (or was at the time) that uncompromisingly serious, like a full-masted ship of iron-willed sincerity, tossed on the savage sea-tides of circumstantial ridiculousness. He doesn’t get the joke. Your criticism means nothing to him. He will stoically sail on and bring that ship to a safe harbor— and get his point across!— with or without your acceptance.

To follow your bliss in defiance of the opinions of others is to experience the purest and rarest freedom one can know in our culturally-opinionated society: the freedom to sincerely and fearlessly express yourself. Even if you can’t sing a note.